Aaron Sanchez can manhandle a right-handed batter with the best of them. For his career, same sided hitters have slashed a less-than-robust .175/.243/.220 in 380 plate appearances. He allowed a home run to Adrian Beltre on May 15th, and that moment is only noteworthy because it represented the first dinger that he had surrendered to a right hander in his Major League career. For good measure, through a trio of starts, he hasn’t allowed one since. This fantastic information was raised as a counterbalance to what had been a horrendous struggle for the young Sanchez as he attempted to find his permanent home in Toronto: the left handers.

It was a crippling vulnerability, and led managers to stack their lineups with lefties at every opportunity they could. In 2015, between the bullpen and the rotation Sanchez faced 380 batters, and despite most estimates having just 25 to 30 percent of baseball players as lefties, our right hander was facing them over 53 percent of the time. This was done because they were hitting a healthy and full-bodied .279/.390/.488 against Sanchez. Josh Donaldson, last season’s American League Most Valuable Player, is a career .274/.354/.492 hitter. Let that sink in for a moment. It was a massive concern as the rotation versus bullpen debate commenced anew in February, but as Sanchez turned in dominant outing after dominant outing in Spring Training, rightly or wrongly, the apprehension quieted. Andrew Stoeten wrote an excellent commentary on his results towards the end of March, noting that, while you can’t criticize him for not having the most imposing lineups opposite him, the best left hander he had faced throughout the entirety of spring was the Mets’ Michael Conforto, and after him, there was another considerable step down in talent. With a full head of steam behind him, Sanchez was officially named the fifth starter less than a week later, but Stoeten’s piece brought to light a key element worth monitoring as the season unfolded.

We’re now eleven starts into his 2016 season, and the reason Sanchez versus lefties hasn’t been a story is simply because it hasn’t been a story. He’s still facing them significantly more often than not (58 percent of total batters faced in 2016), but as a group, they’re hitting just .232/.308/.355. In this modern age of advanced metrics, OPS is something of a rudimentary number, but watching it be shaved by over 200 points (.878 to .663) has been marvelous to behold. He has continued to be better against right handed batters (.229/.286/.308), but with his power two-seam fastball that’s not likely to ever change. The greatest barrier standing between Sanchez and a future silenced of the “reliever” label was attaining adequate status against opposite handed batters, and at least through two months, he’s attained it.

The how is where things really get interesting.

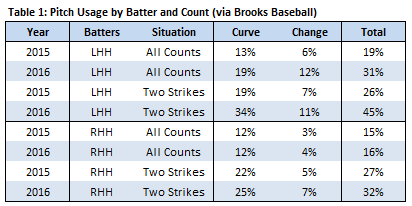

While his two-seam fastball is a dominant pitch, everyone knew that Sanchez would need to find trust in his curveball and changeup if he was going to survive – or even thrive – against left handers. Early season data suggests that some level of comfort has been achieved; his overall curveball usage has increased from 12.5 percent in 2015 to 16.4 percent in 2016, and his changeup has followed suit increasing from 4.3 to 8.9 percent.

The usage patterns are even more evident when looking at splits by batter handedness. As he’s wont to do, Sanchez has pounded right handers with 85 percent hard-stuff this season (a mirror of last season), but against left handers, his approach has evolved considerably. His curveball and changeup accounted for a total of just 19 percent of pitches thrown in all counts to lefties last season, but has climbed to 31 percent in 2016. The adjustments are especially pronounced in two-strike situations, where the usage has jumped from 26 to 45 percent, driven primarily by the curveball.

At 7.96 per nine innings, Sanchez has struck out batters more frequently this year than he has in any season since he was a member of the Lansing Three-headed monster (with Noah Syndergaard and Justin Nicolino) back in 2012, and at least some of his success can be attributed to the approach change with two strikes. Curveballs will always induce more swings-and-misses than fastballs, and in addition to generating more overall, the whiff per swing rate of his curveball itself has increased from 27.6 percent to 36.6 percent here in 2016. Sanchez has accomplished this in two ways: via tighter rotation and through better planning and execution – the latter of which is a feather in Russell Martin’s cap.

The curveball has averaged 78.5 miles per hour this season, down from 79.9 in 2015, further expanding the velocity gap between it and his blazing fastball. Both the horizontal movement and vertical movement have increased considerably relative to 2015 as well, but the most pivotal element may be the spin rate. After averaging 1,846 revolutions per minute last season, Sanchez has throttled the curveball up to 2,097 rpm (both figures via Texas Leaguers). The public understanding of spin rate is still in its infancy stages; some data sources extrapolate spin rate based upon movement while others have the technology to measure spin rate based on observed rotations, and just as crucially, we’re still attempting to find the best way to utilize the data. For one example, Alan Nathan wrote an interesting but very technical article on Baseball Prospectus last year which showed that while pitches like fastballs and changeups have almost entirely “useful spin”, breaking balls like curveballs and sliders carry “gyro spin” or non-useful spin as well, and the ratio between the two types can be just as important as the raw spin rate itself.

Sanchez has always had a great curveball, and while making it even tighter certainly can’t hurt, the bigger issue was commanding the pitch and getting batters to chase it. His O-Swing rate with the curve was just 25.2 percent last season, which was well below the league average of 30 percent for all pitch types. In 2016, it has jumped all the way to 37.3 percent, and it’s because the battery of Sanchez and Martin has set batters up for it magnificently.

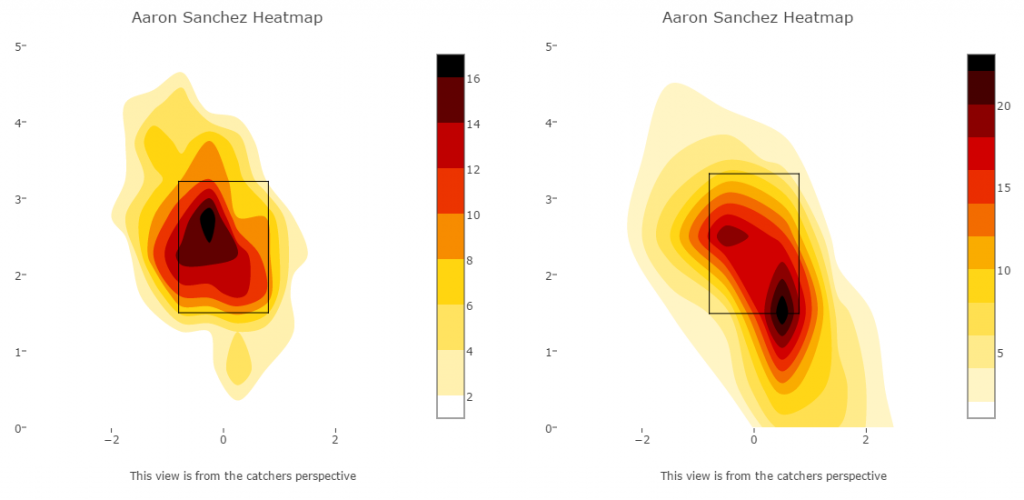

The two heat maps above (via MLB Savant) show Aaron Sanchez’s usage patterns versus lefties this season with his two seam fastball (left) and curveball (right). The movement of his two seam fastball carries it away from left handed batters, and he’s used it predominantly on the outer half of the plate to ensure the pitch doesn’t break into their swing plane. He has also started seeking out called strikes down-and-inside as we saw in Wednesday night’s start against the Yankees, and while he was robbed by a half-dozen missed calls by the umpire, both of these locations setup his curveball to great effect.

Sanchez has targeted two areas against lefties with his curveball, both of which are complementary to the fastball locations above, and both of which serve very different purposes. When he throws a curve to lefties early in the count, he’s often seeking a called strike on the outer half. The batters see the pitch starting outside and they likely assume it’s a fastball that is going to carry well outside. But the curveball moves seventeen inches horizontally in the opposite direction relative to his fastball (+8.35 versus -9.09 inches), and tucks in over the outside corner. Sanchez even appears to be making a concerted effort to keep the curveball elevated in these situations, and while that could cause a lot of trouble if batters are looking for it and it creeps too far in, it’s a tremendous boon to his deception when they’re not. The GIF below (via @BadNewsJays) shows Corey Dickerson of the Rays taking an elevated, outside curveball in a 1-1 count for strike two, and you can tell he’s surrendered any swing consideration when the pitch is about halfway to the plate. In fact, he’s come completely out of his stance by the time Martin catches the ball.

Sanchez threw the outside curveball to lefties quite frequently in 2015 as well; what he didn’t even attempt to do was throw at the back foot of lefties. It’s unusual that he seldom went to this location because with a sharp breaking ball like his, low and inside is one of the best places to attain whiffs against opposite handed batters. “Why not?” is a question better asked by those with locker room access, but the most likely explanation is that it’s a dangerous area to target with shaky command; release too early and the pitch is center-cut and moving into their swing plane, release too late and it’s probably a wild pitch or hit batter. Sanchez didn’t appear to have the requisite trust level in his curveball last season, but an offseason of hard work has paid dividends. The right hander has found that comfort and command, Martin has obliged with his game calling, and the duo have been heartless in their ruthless pounding of the back-foot curveball. Words are a fantastic medium, but sometimes it’s better to let the awkward swings of Joe Mauer and Didi Gregorius do the talking.

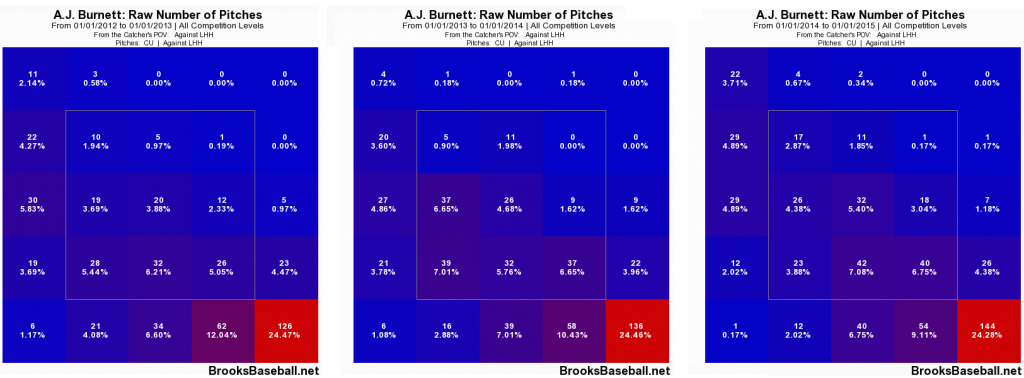

This combination of curveballs might best be described as the Clint Hurdle/Russell Martin special, and it was used by one of the pitchers to whom Sanchez is most often compared: A.J. Burnett. Left for dead by the Yankees after disappointing 2010 and 2011 seasons, Burnett was traded to the Pirates and rebounded with a very good 2012 season. Martin joined the Buckos in 2013, and with him behind the plate, the then 36-year old Burnett had one of the best seasons of his career. He led the National League in strikeouts per nine innings at 9.85, and behind the scenes, Hurdle and Martin had clearly been making tweaks to his curveball approach against lefties. In 2012 with the Martin-less Pirates, Burnett threw 11.1 percent of his curveballs to lefties on the outer third of the plate, and 24.5 percent down and in. With Martin on the Pirates in 2013, Burnett increased his outer third usage to 14.6 percent while maintaining the 24.5 percent back-foot rate. Separated from his former battery-mate after signing with the Phillies for 2014, Burnett’s curveball location usage dropped back down to 11.1 and 24.3 percent, respectively.

While I’m sure there are countless other instances of right handed starters following this playbook against lefties, it’s interesting that the pitcher to whom the public draws the most frequent parallels for Aaron Sanchez also found his greatest success with Sanchez’s current catcher, and Sanchez’s current curveball approach. Baseball is regarded as the game of adjustments, cascading one after another as hitters and pitchers figure things out in alternating succession. What’s most fascinating about Aaron Sanchez’s latest adjustment is that, if he maintains this new found command, there’s just no counter adjustment that the opposition can make. The threat of a 95 mile per hour fastball is always looming, and because Sanchez has shown the ability to locate it with deadly precision on the inside corner, lefties are helplessly in protect mode. Sanchez’s development has made it a coin-flip with two strikes, and with a Euclidean distance of 29.142 between the fastball and curveball, the two pitches are about as far apart as you’ll ever see. Guess heads and get tails, and you’re simply not going to make contact.

Lead Photo: Nick Turchiaro-USA TODAY Sports