“If you believe your catcher is intelligent and you know that he has considerable experience,

it is a good thing to leave the game almost entirely in his hands.” - Bob Feller

DUNEDIN – Catcher defense is an interesting thing. When trying to evaluate it, most of the talk has shifted towards pitch framing (or receiving), with cursory mentions of “controlling the running game” and blocking ability. This makes some sense, as we have data to quantify all of these things. But if you were to ask most catchers, their primary objective is guiding a pitcher through the game – pitch calling.

As a pitcher, this area of the game has always held the deepest fascination for me. There is something truly unique in the battle between the batter and the battery, yet it often goes completely unnoticed by anybody but the most die hard of baseball fans. In an effort to correct that, I talked to the Blue Jays catchers (and a pitcher) to see how they approach this esoteric segment of the game.

For Russell Martin, everything begins with communication:

“Most pitchers – young or old – have a good idea of what they like to do when they go out on the mound…just talking to the guys is the first aspect of my preparation; I feel like it helps build the chemistry with the player itself; just listening to what Marco has to say, just listening to what Stroman likes to say, listening to what the pitching coach has to say too. Everybody’s got information and my job is to keep the information that’s helpful to me and what I’m trying to accomplish.

It’s a simple enough concept to get your head around: Ask the guy what he wants to throw beforehand, so that things go much smoother in the game. But communication doesn’t just mean asking, “what do you want to throw?” If that were the case, there would be no such thing as a good pitch calling catcher. Communication also means knowing when to put your foot down.

For the most part, a catcher will suggest a pitch and the pitcher will throw it. If the guy on the mound wants to throw something else, they’ll shake off and the catcher will suggest a different pitch. However, that’s not always the case.

“There are times, [and] it’s not often, where your gut will tell you, ‘ugh, I don’t really feel like it’s the situation’ or you feel like a hitter is sitting on a certain pitch and that’s the pitch the pitcher wants to throw. There are times where time needs to be called and you need to have a quick conversation with the guy on the mound.”

“I’m just trying to help them, or guide them through a game, using what they have that day.”

Even that is a fine line, however. There are considerations beyond simply getting to the ‘right’ pitch for the situation:

“You have to be very intuitive when you go talk to [the pitcher]…the best pitch is the one that’s going to be thrown with conviction. So if the pitcher really believes in the pitch that he’s going to make, it’s probably the best pitch. Because if I go up there and I talk to him and say, ‘hey, I was thinking this’ and he just goes off what I was thinking, but he doesn’t throw the pitch with conviction, then it’s not necessarily the pitch that I was thinking anymore.”

That’s something we hear about with occasional frequency on the broadcast, but never really much in depth. It can be difficult to get your head around the idea that merely suggesting a curveball when the pitcher was thinking fastball could mean you get a bad curveball instead. People expect that a major league pitcher should have confidence in all of his stuff. Martin agrees, noting that it’s “the job of the pitcher.” However, while a pitcher can try to make himself believe it, “sometimes what we say as people is not necessarily how feel inside.” In fact, Marco Estrada had to teach himself to trust all of his stuff as recently as last year.

Communication matters and it’s more than just talking to someone; you have to know just what to say. Martin happens to be one of the best in the game at reading pitches, so when he talks, pitchers listen. We saw some evidence of this last year with J.A. Happ.

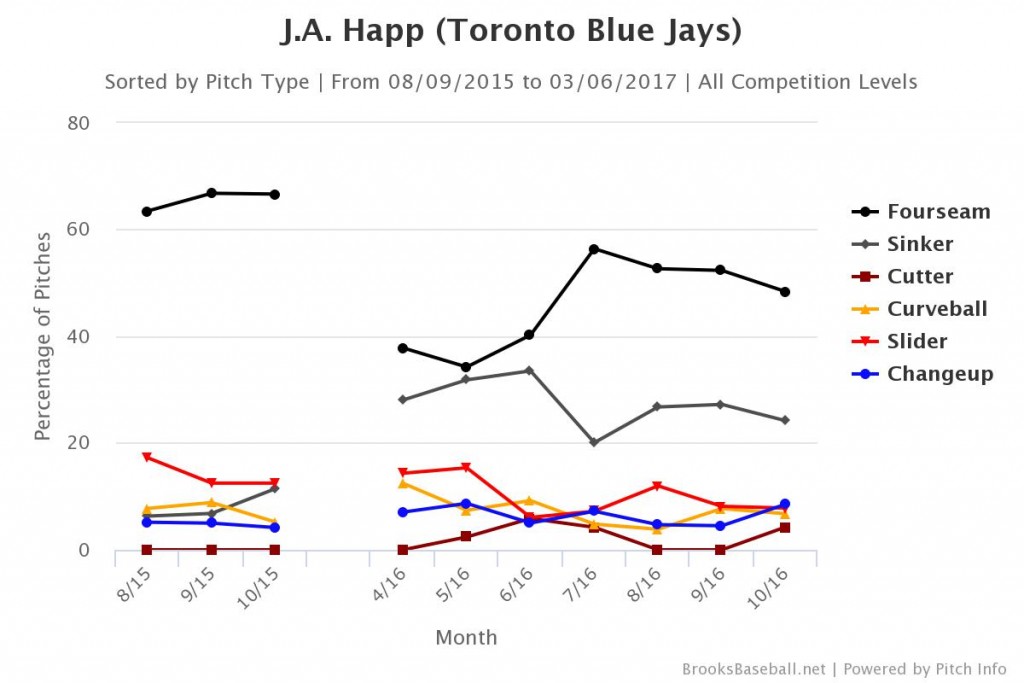

The tall lefty was coming off one of the best ten start stretches a pitcher can have, posting a 1.37 ERA and 9.6 K/9 through the end of the 2015 season with Pittsburgh. He had that extreme success while throwing an inordinate number of fourseam fastballs. Yet right from the get-go, Martin was calling way more twoseamers to go with that fourseamer.

It wasn’t just some random experiment, either. Martin knew what he was doing:

“[Happ]’s able to locate that fourseam fastball up and in on righties’ hands and then the two-seamer, it’s a pitch that’s moving out of the zone at the bottom of the zone. So, having to cover the up and in and then down and away; one moving away from you, the other one boring in on you. That’s TOUGH to do. You can put a ball that’s not moving in those spots and they’re hard to hit, right? So if you can get a little velocity with that and a little movement, it’s even harder.”

Without that read from Martin and then the ability to get that across to Happ, we may have only seen fourseam Happ all year. Thankfully, he and Martin were on the same page. Happ:

“I was focused a little bit on mechanics and just being aggressive in Pittsburgh. And here I just started tinkering a little bit – trying to keep that same mindset, but also keep that two-seamer because I know in the past that has been a big pitch for me.”

“I always say [the pitcher/catcher relationship] is an underrated thing and it’s nice to have a spring training – especially when you’re on a new team – to get to know that new catcher and develop that relationship. They know how you pitch, how you work, how your stuff works and plays. That’s huge to have a guy who understands that.”

The results speak for themselves, as Happ had easily the best season of his career, very heavily due to his pitch mix. However, when I mentioned Happ’s unique fastball movement and asked if it was part of the decision to change things up, Martin wasn’t fully aware:

“I felt it, but I didn’t know that…I’m glad there are people out there that are gathering that information and giving it a numerical meaning and explaining why it’s effective. For me it’s more of an instinctual thing. What I’m seeing from behind the plate is guys not hit the ball hard and guys having a hard time catching up to it. And it’s like a more simplistic way, but then if you want to quantify it with data, that’s great – I’m all for that.”

It makes some sense. As a catcher, it’s Martin’s job to see the pitches and, “[try] to stay one step ahead…finding out what works in certain situations against a certain type of hitter.” He needs to be able to read the swings and the quality of the pitches with his eyes, even if PITCHf/x data might suggest something else. Essentially, raw “stuff” isn’t the major factor when it comes to Martin’s pitch-calling:

“A pitcher can have a nasty cutter, but if that cutter is down the middle a lot, there’s a good chance hitters are going to get good swings on it. Then I don’t know what the numbers are on that pitch, but I don’t even need to know the numbers. I’m like ok, if this guy makes mistakes with this pitch often in the middle of the plate, it’s not a high percentage quality pitch. But if he has another pitch that he locates and when he misses, he misses off the plate – and when he gets it, it’s in a hard area to hit with any power… There are certain pitches that are just tough to hit.”

“In all honesty, every pitcher has strengths and things he’s not as good at. I wouldn’t call them weaknesses, because every single pitcher’s pitches are good. There are just certain pitches that they command a bit better, that they have more confidence in. And you have to know your pitcher.”

So while Martin appreciates our attempts to see the why, it seems he prefers to trust his own intuition. He makes the best selection with what his eyes tell him – monitoring stuff, location, and hitter swings – but not the numbers. It has gotten him this far, so there’s no reason to doubt it. But even if he doesn’t know it, he is still subconsciously embracing the data and passing it onto the next generation. When I spoke to catching prospect Reese McGuire, he had this to say:

“We’re constantly trying to learn as catchers and Russell and [Jarrod Saltalamacchia] have both been tremendous with leading that.”

“I think that [PITCHf/x data and Statcast] is the next step – that’s the next level – when they’re going to have a little bit more information. I’ve already heard Russell and Salty talk about that too, where a certain pitcher, he’s coming from a certain side of the rubber and he might not get a certain call percentage wise, say he gets screwed on a strike because of the angle his ball is coming across the plate.”

That was very fun to hear, as it’s not something we ever really consider when looking at whether a pitch was called correctly. We tend to blame the umpire or credit the catcher’s receiving, but it sounds like it’s also a big part of the catcher knowing what pitches are easier and tougher for an umpire to call correctly and then calling pitches in or away from those locations. That information can be huge in getting or not getting strikes in key spots.

Pitch sequencing is a constant game of cat-and-mouse, with the pitchers and catchers trying to outsmart the best hitters in the world. Get this guy to reach for this, or to totally misread that. Change your angle on this to make him miss that. It’s fascinating to watch and just as fun to learn. Martin is the professor teaching a master class.

“My goal…is to stay one step ahead and find out what works in certain situations against a certain type of hitter. The game changes – the hitters are trying to make adjustments too – and there’s not just one right call I can make, but as long as I know my pitcher and he believes that I know him and we feel confident together, then we’re a better team.”

A better team? That’s a good call.

Lead Photo © Kim Klement-USA TODAY Sports

Good stuff. Having caught a little in amateur ball, I can vouch that even at that level, pitch-calling is more involved than many people appear to realize.

Yeah, for sure. As a pitcher, I absolutely notice the differences between catchers and their approach.

Fascinating stuff Joshua, thanks for this.

Thanks!