J.A. Happ has been nothing short of a revelation in 2016. He currently has a strikeout rate of 22.2 percentage on the season (32.4 percent since the start of July), sits second in major league baseball with 17 wins, and has an ERA that has hovered between 2.80 and 3.20 all year long. All of those would be career bests in seasons during which Happ was a full-time starter. He has unquestionably been one of the better pitchers in the American League. The question that seems to be on everybody’s mind is “how?”

Like Marco Estrada last year (and continuing into this season), J.A. Happ is succeeding to an insane degree despite stuff that, on the surface, seems decidely mediocre. His fastball has league average velocity (approx 92 mph), and none of his offspeed pitches have any sort of extreme break or speed. So again, how is he getting hitters out with such extreme ease?

The basic answer is that his stuff isn’t quite as mediocre as it looks on the aggregate. The better answer involves a bit more nuance. He is constantly figuring out better ways to use that stuff, and becoming more effective every time. In fact, despite many (includng me recently) assuming he has just gone back to his Pittsburgh ways, we are actually looking at yet another new incarnation of Mr. Happ: J.A. Happ 4.0. Let us dive into the mystery that is this lanky lefthander’s success.

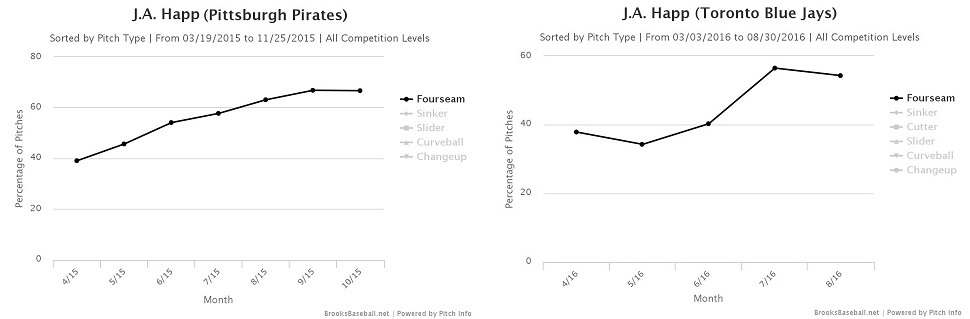

Considering the way he pitches, any discussion on J.A. Happ has to begin with his fastball. As you may have seen elsewhere, Happ has become increasingly reliant on the fourseam fastball as the season has gone on, which follows a trend from his time last year with the Pirates.

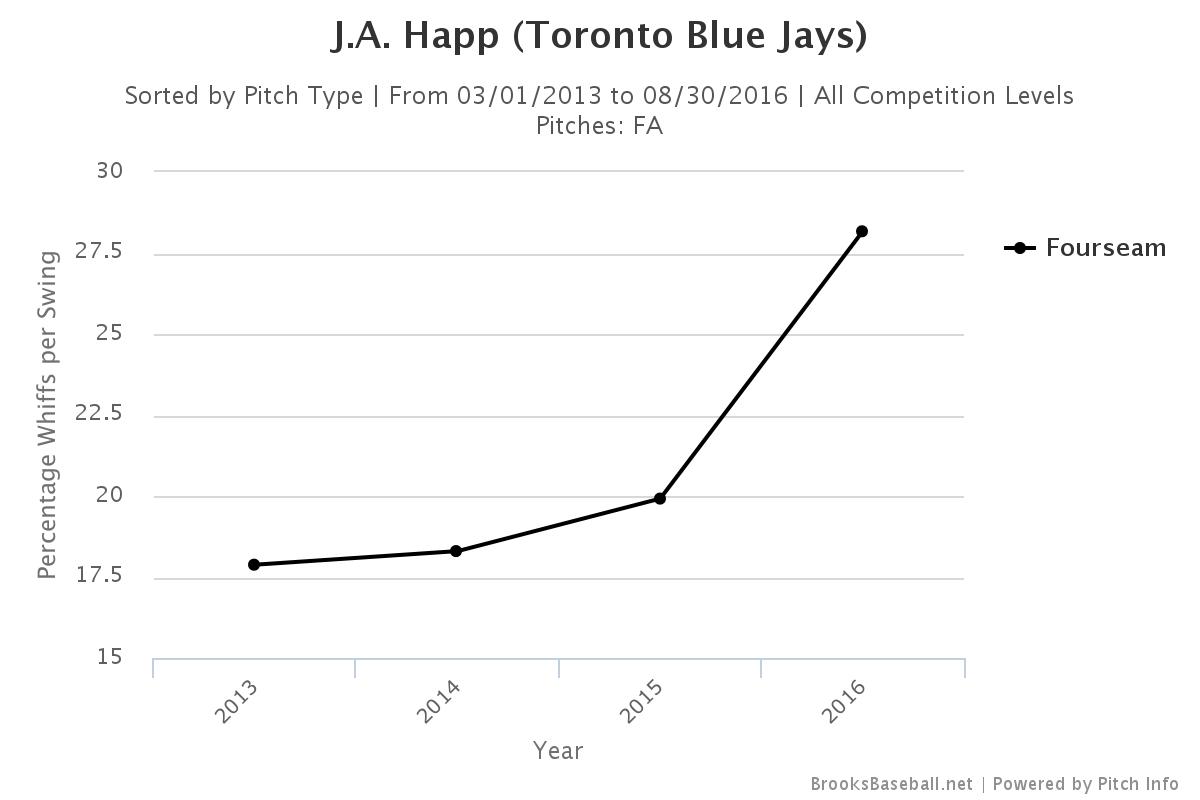

The spike in fourseams has directly coincided with a spike in his strikeout rate, which has led many to believe it is the sole cause for Happ’s current bat-missing ways. This is certainly backed up by the numbers; among pitchers who have thrown at least 500 fourseam fastballs, J.A. Happ sits third in miss rate on the pitch, at 28.8 percent of swings. That rises to number one in all of baseball if you raise the minimum to 1000 fourseam fastballs. That’s pretty impressive. However, this whiff rate also happens to be an extreme outlier:

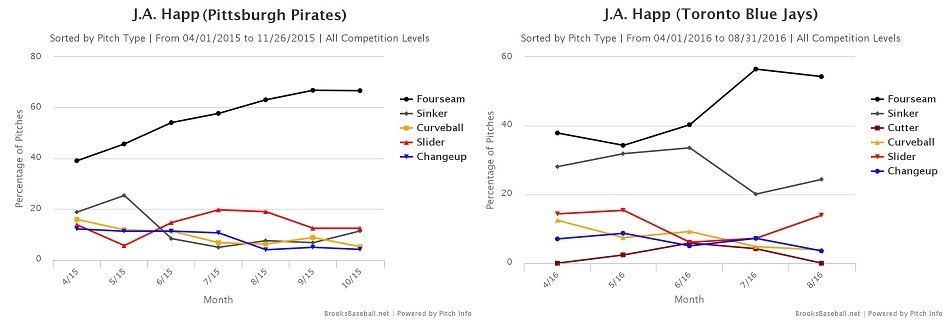

In the last three years, Happ has never topped 20 percent. Even if we just filter out his time with the Pirates, he was still just missing bats 21 percent of the time, and that included facing opposing pitchers. As a result, merely throwing more fourseam fastballs isn’t the main reason for the uptick in strikeouts. However, when we put the rest of Happ’s offerings back into the mix, the picture gets a little bit clearer.

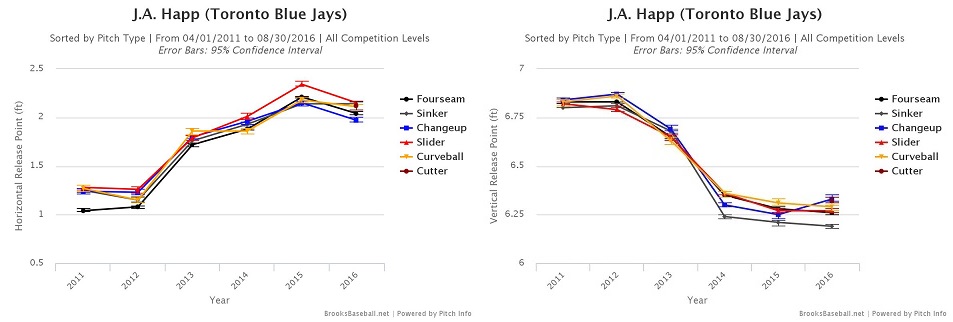

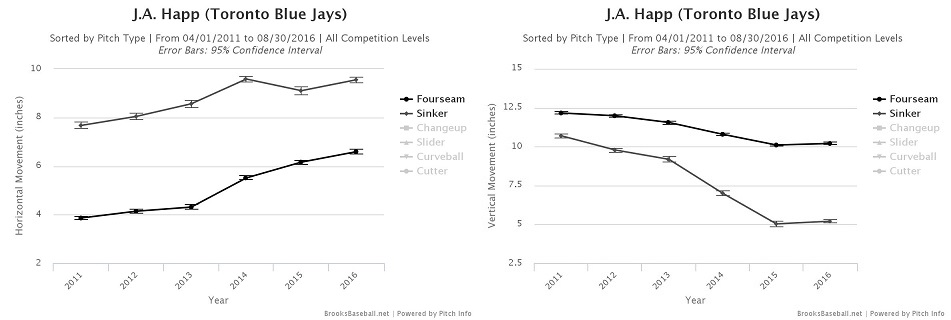

As you can see, Happ may have started throwing a lot more fourseamers, but unlike last year, he is still throwing plenty of sinkers as well. Of course, simply throwing more sinkers doesn’t explain a nearly 50 percent increase in whiff rate. In order to understand fully why increased sinker usage is leading to more swings and misses on the fourseamer, we must first take a quick stop in the past and look at a mechanical change Happ made during his first time in Toronto. Before the 2014 season, the Blue Jays dropped J.A. Happ’s arm slot in an effort to help him get more movement on his fastball, as graphs explain.

The team lowered Happ’s release point by nearly half a foot, and he also began releasing farther away from his body (see tables above). The attempt definitely worked, as Happ’s fastball immediately started getting more shape. His two seamer started dropping over two inches more and getting an inch of extra run. The fourseamer still stayed up – only dropping an extra inch – but also picked up that inch of run. In the last two years, however, Happ has taken that to the extreme:

Happ is now getting an inch of extra run on the fourseamer, while the pitch is still staying up at the same high rate. The two-seamer is the big winner, though, having taken a gigantic step forward. The offering is now getting another two full inches of extra drop, while still maintaining the 9.5” of arm side run. That horizontal break places him in the top 10 of all pitchers, ahead of even Aaron Sanchez.

The tailing action is certainly nice, but what is most important is that extra sink. By adding those two inches to the two-seamer, Happ is now seeing a full 5” difference in vertical break between his fourseamer and his sinker. That places him number one in all of baseball in break difference among pitchers who threw at least 500 of each pitch.

That is why the increased sinker usage matters. With Pittsburgh, the improved command and consistency were enough to get outs. This year, batters are constantly being forced to adjust to two pitches that come in at essentially the same velocity (the difference in speed is less than one mile per hour), but with a bigger difference in how they move than any other pitcher in baseball. As a result, the fourseam has the elevated whiff rate; batters swing under it expecting it to drop like the sinker. When Happ uses both fastballs together, he succeeds.

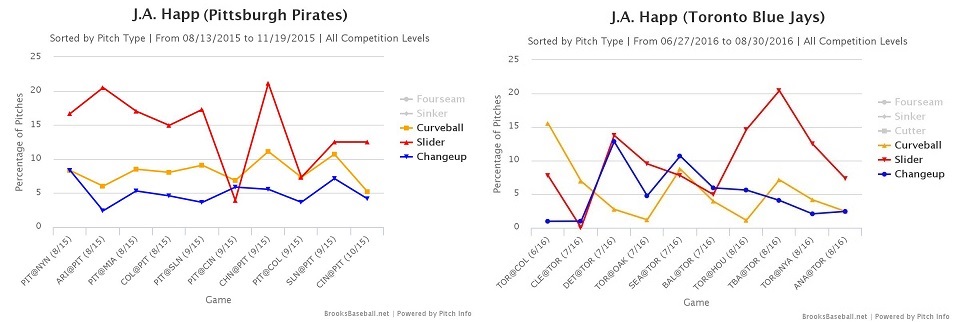

Clearly, the fastballs are far better than average velocity alone would suggest. However, Happ still throws enough non-fastballs that we need to look at them as well. The actual pitches themselves show very little difference from this year to last. In fact, the only one with a noticeable change in shape or movement is the slider, as it has become much more of a cut fastball. But it’s not the break that matters here; we’re going to look at how he is using them. If you remember the roto reviews that we were doing earlier in the season, you may have seen us mention on multiple occasions just how unpredictable Happ had been. It was impossible to tell from one start to the next just what he would throw. One day it would be more sinkers and curveballs, the next it would be fourseamers and changeups, or sliders and curveballs. There really was no way to guess what version of Happ you were going to see. As such, he was able to succeed by getting weak contact instead of swings and misses.

He did something similar in Seattle at the outset of last year as well, and was looking like an All-Star. Then for some reason he decided to stop throwing sinkers at all in mid-May, and started getting hit. At least he was still mixing his breaking balls, though. By the time he became fastball happy in Pittsburgh, there was a very clear hierarchy of Happ’s off-speed stuff. Compare that to the current version of fourseam-heavy Happ (start vs Colorado was the first time Happ went over 50 percent fourseamers):

At no point with Pittsburgh did Happ throw more changeups than curveballs, and only twice was the slider not his clear go to breaking ball. He was always hovering around ten percent usage with the curveball and sat at close to five percent usage with the changeup. With the Blue Jays, there is no pattern at all. In fact, every single pitch has a usage range of over ten percentage points. Even with the increased fastball usage, hitters still can’t know what’s coming from one pitch to the next.

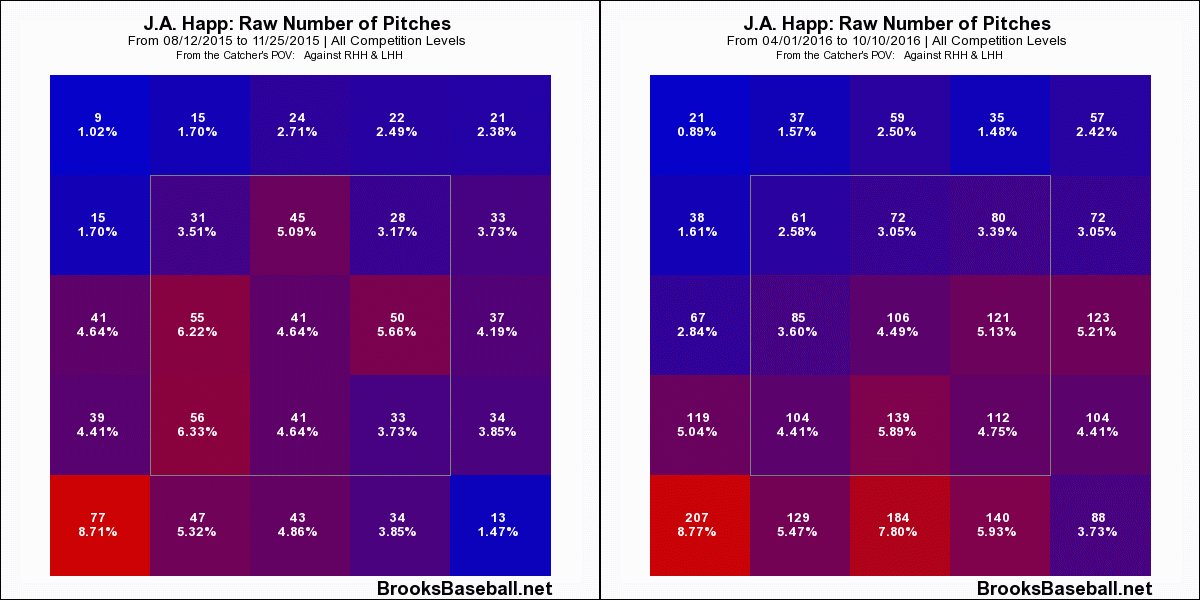

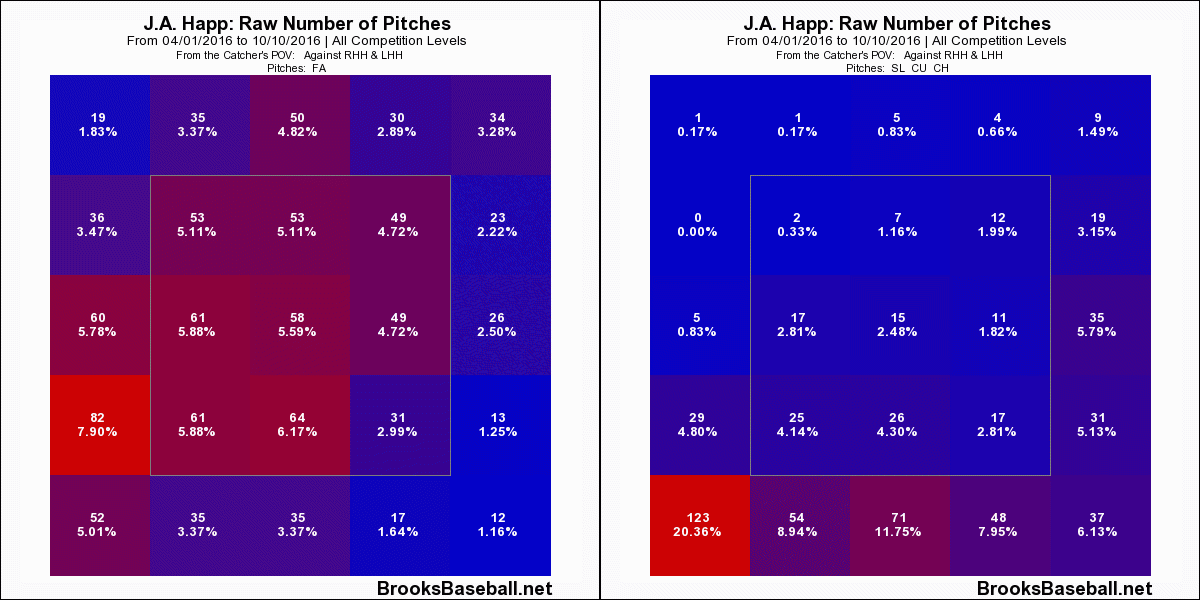

This change in patterns just so happens to apply to where Happ throws the ball, as well (Pirates numbers on the left):

From the looks of that grid, J.A. Happ is working down in the zone much more often than in his brief stint with the Pirates. Combined with the increased sinker usage, this is a good reason for a slight uptick in his overall groundball rate, and it makes it hard for hitters to elevate the ball for extra bases. This is where the unpredictability comes in: When Happ gets to two strikes, he works up in the zone with his fastball instead (see left grid below). In 2015, that would look just like every other fastball he was throwing. Now it’s coming in on a completely different plane. This is forcing hitters to react to a pitch in a location they’re not seeing at other points in the at-bat. That leads to strikeouts. In addition, while hitters have to be aware of that high fastball, Happ also works down in the zone with all his other offerings (see right grid below). By forcing the hitters to cover the entire stike zone, Happ makes all of his pitches pitches play up. As a result, every single pitch has an elevated whiff rate.

To recap, we have a pitcher using his supreme fastball variance to generate strikeouts and groundballs for the first time, an unpredictable off-speed usage to create overall weak contact, and a pitcher who works down in the zone (avoiding power), except for when he elevates for a strikeout.

J.A. Happ has taken what he learned with the Pirates, and along with Russ Martin and Pete Walker, evolved it over the course of this season to turn himself into one of the elite pitchers in the game. He could’ve just continued throwing the way he did in Pittsburgh that dominated the NL Central, but he wasn’t satisfied with that. And then could’ve kept up the way he was mowing down the AL East in the early parts of this season, but he wasn’t satisfied with that either. He keeps adjusting. That, above all else, is why I believe in J.A. Happ.

I can’t wait to see the next version.

Lead Photo: John E. Sokolowski-USA TODAY Sports

Great article man. Keep the pitching break downs and analysis coming. It’s fascinating to see people like you and the guys at FG dig into the numbers behind why pitchers with “average” stuff can be as effective as the Kershaws, Prices and Arrietas of the league.