Back in September, Matt Trueblood wrote a fascinating piece for Baseball Prospectus exploring why many pitchers are ditching sinkers, relying instead on fourseam fastballs. You should read it for yourself, but the general point is that in addition to combating hitter adjustments to the sinker, the fourseam just interacts much better with traditional offspeed/breaking pitches.[1]

The article made a number of good points, all of which I agree with, but it also left out one pitch comparison that far too often gets ignored: how the two fastballs interact with each other. So while Matt’s piece makes a ton of sense, there is still a small subsection of pitchers to whom it should not apply. This has been an area of particular fascination for me since I broke down the way J.A. Happ uses both of his fastballs to help his mediocre arsenal play up. Then in the 2016-17 offseason, I turned that look towards Marcus Stroman and his unique set of fastballs.[2]

The basic premise of those pieces was that pitchers with high variance in the movement between their fastballs can make both pitches play better by mixing them liberally. Essentially, hitters are trained to hit balls that move certain ways because they see so many. When balls move in ways they do not expect, it makes it much tougher to square up. That can be an individual pitch with unusual break, or in this case, an anomalous split between two pitches. In essence, I’m talking about outliers. So because of those two Blue Jays, I wanted to see which other starters could get the same sort of benefit from changing their fastball usage: the other outliers. We’ll call this the Velasquez/Happ corollary to Matt’s piece, which you’ll understand when this is finished.

The first order of business was to compile a list of all the starters who threw at least 50 fourseamers and 50 sinkers in 2017 using BP’s PITCHF/x Leaderboards.[3] That gave me a sample size of 164 pitchers. Using this list, I determined the means and standard deviations for horizontal and vertical movement for both fastballs, as well as for the break difference when the pitches are taken together.

That sample was too large, however, as it failed to take note of the second thing that Matt mentioned as contributing to the decline in sinker usage: injury. He referenced Mike Sonne’s fatigue units, which suggest that repeated pitches at high velocity lead to fatigue (and therefore eventually injury). The argument is essentially that one should be throwing fewer fastballs, and that given the relation to offspeed pitches mentioned previously, the fastball that should be ditched is the sinker.

It’s hard to argue with that, so instead I’m going to focus on those who still throw at least 54.5% fastballs.[4] That gives us the following table of 79 starters. Each of these pitchers below threw at least 54.5% fastballs and at least 50 each of sinkers (listed as twoseamers) and fourseamers.

For a full page version of the above if you don’t feel like scrolling as much, click here.

There are a whole bunch of columns there, but the most important ones are the final six which look at aggregate changes in movement. There are a few exceptions, which I will discuss, but for the most part, this is where we’ll find the most interesting candidates for improvement through changes in their pitch usage; there are some pitchers whose fastballs move in such extremely different ways that they stand out from the crowd, including a few whom I want to point out in particular.

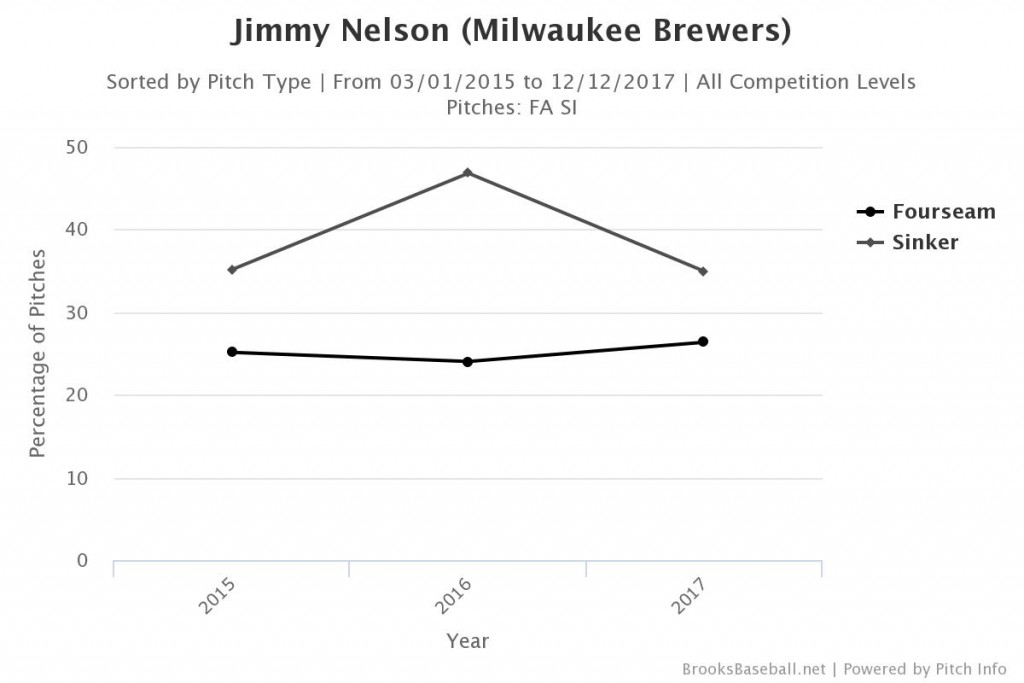

First up is the Brewers’ Jimmy Nelson. After a reasonably successful 2015, in which Nelson made tremendous improvements on his sinker, he started throwing it more than ever in 2016. It didn’t work out though as he gave up an extra hit per nine innings over the year before and more walks than ever despite more overall pitches in the strike zone (50.8% vs 48.0% in 2015). Then, despite getting even more drop on the sinker, he once again started using his fourseamers and sinkers with a much more similar frequency in 2017.

By any measure, Nelson had easily the best season of his career last year before getting hurt diving back into a base. Some of that improvement is definitely due to increased control (53.1% in the zone in 2017), but he also started missing more bats. Hitters made contact on just 76.9% of swings, down from 83.3% (but closer to the 78.6% in 2015) and more importantly, he posted career high whiff and whiff per swing rates on both of his fastballs. His chase rate soared as well, from 26% to 33%.

Of course, the success achieved by throwing more fourseamers could suggest that he should ditch the sinker altogether, but the movement on his fourseamer is decidedly average (both the horizontal and vertical movement are within one quarter standard deviation from the mean). If he threw that alone, it would look exactly like what hitters are used to seeing from all other pitchers. Instead, they have to adjust for six inches of break between two pitches, and nearly five on the vertical plane alone (which gives a Z-score of 2.2), with a velocity difference of just 0.3 mph. That would be insanely tough for even the best hitters in baseball, let alone the average. Nelson would also be a very good example for Reds breakout rookie, Luis Castillo, whose fastballs are extremely similar to Nelson’s in both break and velocity difference. Castillo already mixes both fastballs, but he should probably use the sinker even more. He’s basically Nelson with the added benefit of his fastball coming in at 97 mph.

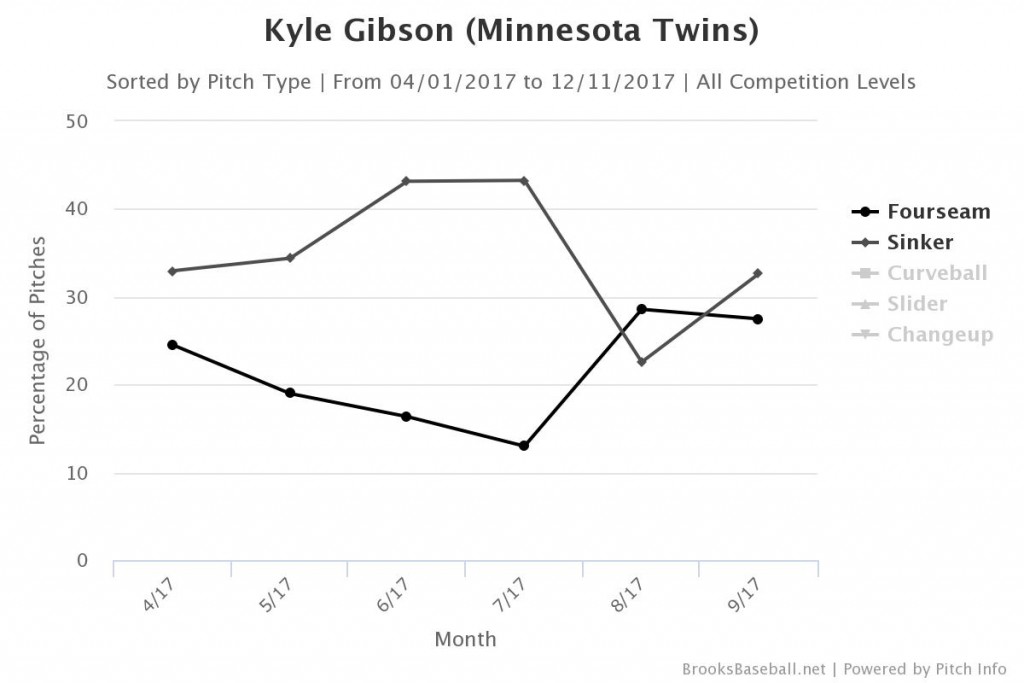

The next name up on the list is Kyle Gibson. Gibson’s change has been written about before (also by Matt Trueblood, coincidentally), but he really altered his pitch usage part way through the year. After throwing predominantly sinkers early in the season, Gibson started mixing in both fastballs heavily starting in August.

His ERA was 6.08 before the switch, 3.55 afterwards. His movement variance isn’t quite as good as Nelson’s, but he does still get over a standard deviation from the mean of horizontal break between the two offerings, while also having average vertical separation, resulting in over five inches of total break difference.

Like Nelson and Gibson, most of the pitchers at the top of this list with a big difference in the absolute break between their fastballs (especially those with extreme difference in vertical break, as that tends to lead to more missed bats) are better served with a healthy mix of fastballs. However, there are a couple of pitchers with large variance in their movement for whom this doesn’t necessarily apply. Marcus Stroman and Clayton Richard are very good examples, as both of them throw a sinker with such extreme outlier movement on its own (over two standard deviations away from the mean) that it behooves them to continually throw it. While they could still get value out of mixing in both and probably miss more bats the way Carlos Martinez does (with a similar sinker), they can still succeed based solely on the sinker.

On the flip side, you have pitchers like Mike Montgomery and Wily Peralta (as starters). Both of those guys should likely be going the route suggested by Matt in his piece. Both pitchers get very little separation between their two fastballs in either velocity or movement and neither of them has a single outlier offering like Stroman or Richard. As such, they should be optimizing their pitch selection to match their other offerings. In addition, some pitchers with high overall break difference but entirely on the horizontal plane, like Dylan Covey (or Tyler Glasnow and the recently signed Tyler Chatwood to a lesser extent), may be better off sticking with more fourseamer usage since the lateral movement isn’t likely to miss as many bats, while also helping their secondary offerings play up.

So now that we have some good cases of this on both sides as well as an exception or two, it’s finally time to get to the ultimate example of how this should work and the reason I called this the Velasquez/Happ Corollary.

Vincent Velasquez’ pitch usage makes absolutely no sense. Here we have a pitcher who has EXTREME outlier vertical break difference between his two fastballs and essentially no difference in the release point between the two offerings (averaging less than 0.1 ft difference in horizontal movement), yet he throws the twoseamer so infrequently that I had to reach back to his 2016 stats to get enough pitches to qualify.[5]

He needs to talk to J.A. Happ. Velasquez and Happ have nearly identical profiles. They both have heavy outlier break difference between their two fastballs, relying mainly on the difference between the vertical breaks as opposed to the horizontal breaks, and they both also have noticeable variances on the pitch velocity, at 2+ mph. But where they differ most is that Happ learned how to use his sinker to achieve success. It’s no coincidence that the two best seasons of his career have been the last two, despite pitching in the hitters park that is Rogers Centre and the powerhouse AL East; his 2-seam usage spiked starting in 2015 and his dominance grew out of it. Russell Martin is aware of it, using the variable movement to pound low with the sinker for groundballs and then get swings and misses up in the zone with the fourseamer.

This is what Vincent Velasquez needs to start doing. He’s J.A. Happ from the right side with an extra two miles per hour, but he’s not using his arsenal to its full potential because he won’t use his incredibly valuable sinker. If he starts mixing it up a little bit, he might finally live up to all of that potential.

So there you have it, the Velasquez/Happ fastball corollary.While there are other things that help a pitcher have a better or worse season — notably command (which is why Bartolo Colon is still getting jobs) and overall stuff — pitch sequencing and usage are tremendously important and can go a long way towards helping a pitcher with good stuff become great and a pitcher with great stuff become elite. That’s why I believe Trevor Williams is going to continue to outperform his peripherals and why I think Alex Meyer needs to pick one pitch and stick to it. Pitchers need to look at what their stuff is doing and make a game plan accordingly. If they mix things right, they should improve.

It all starts with the fastball.

FOOTNOTES

[1]Using BP’s pitch tunneling statistics.

[2]In fact, when combined with Marco Estrada’s number one “rising” fastball, the Jays seem to target pitchers with outlier fastball movement.

[3]I used the 2016 stats for Velasquez because his injury-shortened season meant he missed the sinker threshold.

[4]Since that rounds up nicely to 55%.

[5]He also had an odd release point upon return from injury last year which threw off his numbers.

Lead Photo: Tim Heitman-USA TODAY Sports