This past spring, I wrote a piece for this site hypothesizing that the Blue Jays had decided on a new way of targeting pitchers, something I termed as a potential market inefficiency: choosing to go after pitchers with outlier movement on their fastballs.

At the midway point of the 2018 season, it’s clear things haven’t worked out so well. While some of those arms — namely Tyler Clippard, Seunghwan Oh, and J.A. Happ — have had solid years so far, the general underperformance of Blue Jays pitchers has played a major role in the team’s overall struggles this season.

Recently, former BP Toronto writer, Dr. Mike Sonne, wrote a piece for the Athletic ($) in which he explained that the Blue Jays are ignoring a league-wide trend of throwing more breaking balls, especially in hitter’s counts, and that they are paying a price for it. This led me to the premise of this piece: the dangers of hunting for market inefficiencies.

Mike was a guest on our most recent podcast episode, and we discussed the general concept of inefficiencies. Here’s what he had to say:

“When you look for market inefficiencies, you’re essentially trying to find something that other people aren’t paying for. Whether it’s discount shopping or being smart with your money or whatever you want to call it, there’s a reason why it’s an inefficiency. You’re trying to find a surrogate for some other form of success.”

Mike had a good point. The Blue Jays didn’t target players with nasty, bat-missing stuff, as those types of pitchers tend to cost a lot to acquire. The club instead chose to target players whose pitching style could lead to poor contact. Given the league-wide trend of paying for strikeouts, going in the opposite direction seemed to be a good place to hunt for value in a vacuum.

That vacuum is one where fastball movement is constant, unchanging from year to year. Unfortunately, the real world isn’t so predictable. This is where things went off the rails for the 2018 Blue Jays.

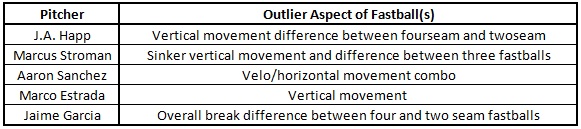

For a quick recap of the original piece, here are the ways in which Blue Jays starters were showing outlier movement:

Of those five pitchers, it’s safe to say that only J.A. Happ has lived up to expectations at all. Sanchez has been mediocre even when healthy, and Stroman, Estrada, and Garcia have struggled to perform. I’m going to look at each pitcher to see what did or did not happen with respect to what made them look interesting coming into the year.

J.A. Happ

Let’s get the good out of the way early. As I’ve written about on this site a couple of times, J.A. Happ gets more vertical break between his fourseamer and twoseamer than any qualified pitcher in baseball. Last year that break difference was 4.9”; in 2016, it was 5.01”. This year, those pitches have a vertical break difference of 5.18”. Nothing has changed, and a recent rough spell notwithstanding, Happ has been exactly as advertised this year.

Aaron Sanchez

Aaron Sanchez hasn’t been on the field all that much this year, though he has still thrown over twice as many innings as he did last year. Even when healthy, though, his overall numbers are definitely down from his elite 2016 that saw him lead the AL in ERA. There are two reasons for this. First and foremost, Sanchez has simply struggled to find his command, going from an 8.0% walk rate in 2016 to 12.6% this year. That would be Sanchez’ highest walk rate of his short major league career, eclipsing last year’s career-worst 12.0%.

That’s obviously a huge problem, but Sanchez has also lost some of what made him so tough to read in the first place. A drop in his twoseam fastball velocity — from an average of 95.1 mph to 94.4 mph — has been accompanied by a slight increase in break (9.38” to 9.66”), but makes the pitch less of an outlier. Last year, the only qualified righty who threw as hard as Sanchez with as much horizontal run was Alex Meyer. If you added unqualified starters, Luis Castillo of the Reds was also on the list. This year, the list has expanded to contain Castillo, Domingo German, Yonny Chirinos, Charlie Morton, and Kendall Graveman. Sanchez has also seen a small dip in the overall break difference between his two fastballs, from 3.6” to 3.3.”

All that being said, the twoseam fastball still leans towards the outlier area of things. The overall difference isn’t that drastic, and thanks to a greatly improved changeup, Sanchez is actually posting the best strikeout rate of his career. If he can just normalize the walk rate, he should be fine.

Now that we’ve gotten those two guys out of the way, it’s time to look at the examples of the true danger of what the Jays have been trying to do.

Marco Estrada

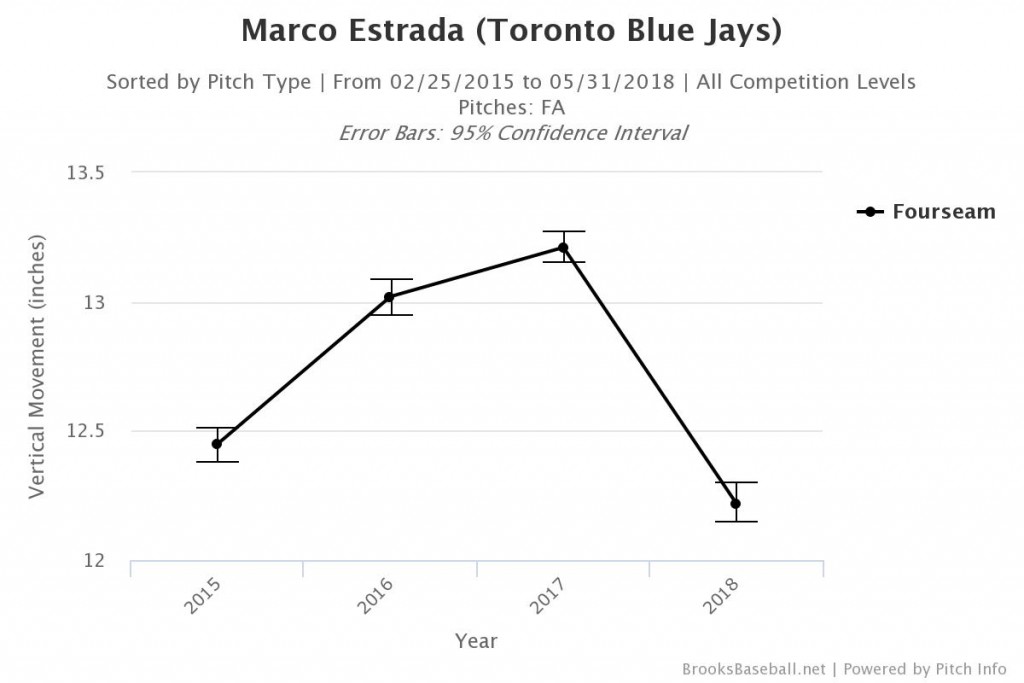

Estrada is a simple case. He throws “rising” fastballs and changeups to get you out, with with a 12-6 curveball to give a different look. He has been doing this for years, and isn’t about to alter that strategy anytime soon. While the changeup is elite, the fastball is what makes Estrada stand out from the rest of the league. However, in the early part of this season, that high-rise heater has lost some of its steam.

From the start of the year until May 31, Estrada’s fastball was fighting gravity to an average of 12.22″ — a notable difference from the vertical movement numbers he posted over the last two seasons. His ERA during that timeframe was 5.68. He did seem to make some sort of adjustment starting in June, though: In the five pre-injury starts since the start of that month (eliminating his one inning outing vs the Mets), Estrada averaged 12.6” of rise, eclipsing 13” twice, and posted an ERA of 2.35.

Interestingly, Estrada’s overall “rise” of 12.34″ on the season (and the 12.22″ early on) is still number one in baseball, and very close to his 2015 numbers. The league-wide pitching environment in 2015, though, was a place where sinkerballers were still in vogue. As such, the 3/4″ drop in “rise,” while still making the pitch an outlier, is approaching what hitters have been getting used to over the last couple of years with the recent trend of throwing high fourseam fastballs.

Estrada’s fourseamer just hasn’t been looking quite as different as it used to. As a result, a few more of those would-be popups have gone for home runs. If he can continue the gains he has shown of late when he returns from the DL, Estrada could rebound nicely and be a good trade candidate for some team needing back of the rotation help.

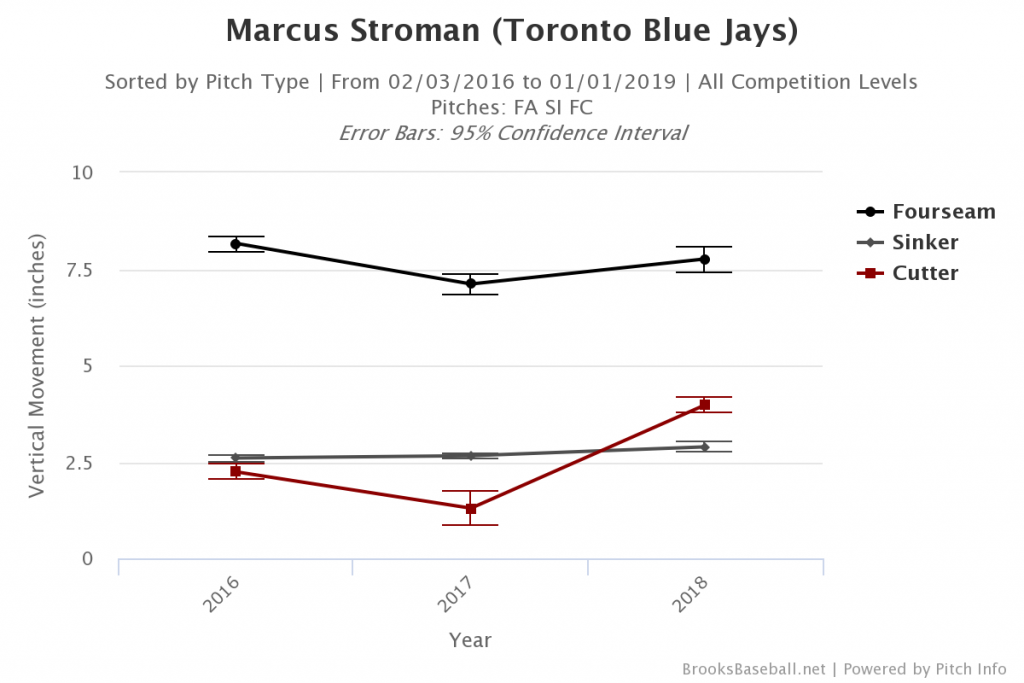

Marcus Stroman

Stroman, like Estrada, has a pretty clear change in his movement profile. Where he once possessed an unparalleled triangular break difference between his three fastballs (cut, fourseam, sinker), that special pitch mix is gone. In 2016, those three offerings covered an overall area of 21.2”. With a velocity difference between all three pitches of under three miles per hour, Stroman saw real success when using all three fastballs in the second half of that season. Last year, the overall area covered by his three fastballs dropped down to the still elite 19.3”. This year, that number has fallen all the way down to 15.3”, thanks in large part to a cutter that is staying up more and cutting slightly less. That reduction in break difference has turned Stroman from a true outlier into someone sitting near the middle of the pack.

All of this is compounded by an over-reliance on the sinker that can at times make Stroman predictable. With his groundball tendencies and the Blue Jays’ shaky infield defense, that can lead to a lot of runs. Stroman still has the stuff to get outs, but he needs to use his whole arsenal more with his fastball advantage disappearing.

Jaime Garcia

The good news is that Garcia still has an outlier break difference between his fastballs. In fact, it has gotten bigger. He has increased the vertical difference from 3.26” to 3.98” while increasing the horizontal difference from 5.52” to 6.24”, and his twoseamer now has the third-most sink among lefties, trailing only Clayton Richard and Chris Sale. Hitters have also missed on 18.06 percent of swings against the twoseamer, the second-highest rate of Garcia’s career.

The bad news: Garcia has lost 1.5 mph on his average velocity, and the extra time hitters have to adjust has led to more takes on borderline pitches. So while hitters are missing the twoseamer more often than usual when they swing at it, the pitch has an overall whiff rate of 7.6%, which is over two percentage points lower than last year. Hitters just aren’t chasing enough. In fact, Garcia’s overall chase rate is at an all-time low, with hitters swinging at just 21.9% of pitches out of the zone. He entered the season with a career rate of 30.2% and a previous career low of 26.6%.

The lack of velocity also affects the type of contact we see in the zone. The increased break difference is great, but if hitters have extra time to recognize the difference in the offerings, they can square up the one that moves less. In this case, that would be the fourseamer, against which hitters are slugging a whopping .767 this year.

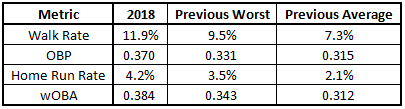

Those struggles, in combination with overall poor command and a plethora of uncompetitive pitches, have seen Garcia post career-worsts in the following categories:

Yikes. Some of this may be due to Garcia’s shoulder problems, and we could potentially see a rebound in the second half. But shoulder issues are nothing new for the lefty, so it’s hard to just dismiss them.

The up-and-down nature of the Jays’ rotation this season is exactly why targeting this specific market inefficiency was actually a very high-risk, high-reward proposition. The possible rewards were easy to see. If these pitchers maintained their stuff and control/command, what seemed like potentially fluky performance could have proved to be anything but.

Relying on a pitcher to maintain his movement and control year over year, especially as he ages, is a tough gamble. And the risk of this gamble was compounded by the Blue Jays’ specific targets: pitchers who, for the most part, rely heavily on their fastballs and that movement to get outs. That was the inefficiency that existed in the first place.

But when that fastball movement is not backed up by something else that can help the pitcher get outs, whether it be elite breaking balls or velocity, you find yourself in a situation where any kind of downturn in the heater will hurt. That’s what led to the problems Mike discussed in his piece for the Athletic: The Jays are throwing more fastballs because they don’t really have another choice.

Does that mean the team should abandon the approach entirely? No. When it works, as we’ve seen with Happ and for 2.5 seasons with Estrada, this method can lead to unbelievable value.

In general, the right play is still to try and find advantages wherever you can. That’s the easiest way to get ahead if you’re limited financially, either from a cheap owner or the presence of bad contracts. You just need to be fully aware of the drawbacks of whatever strategy you choose. Because the more you put it into practice, the more likely it is that one or more players won’t do what you’re expecting.

It certainly hasn’t worked out so far for the Blue Jays in 2018.

Lead Photo © David Richard-USA TODAY Sports