The Blue Jays have been struggling lately. You don’t need me to remind you of that. Let us instead turn our thoughts back to a brighter time. A better time. The year was 1977. The Jays were brand new, and they were god-awful.

Like most expansion teams, the Jays put up an extraordinarily bad debut season. They went 54-107 — the worst record in baseball, and a full 45 ½ games back of the division lead. That division lead was held by none other than the New York Yankees, who with their 100-62 record went on to win both the pennant and the World Series.

The Jays, unsurprisingly, had a losing record against the Yankees that season, though six wins in 15 games could be considered a success given the massive gulf in talent level that separated the two teams. Still, the wins were mostly narrow, and the losses mostly enormous. In their final three-game series of the season, for example, the Jays were swept by the Yankees, scoring a meager three runs to New York’s 22. These were not evenly matched competitors. This was a 100-win powerhouse playing a roster that was, at best, marginal.

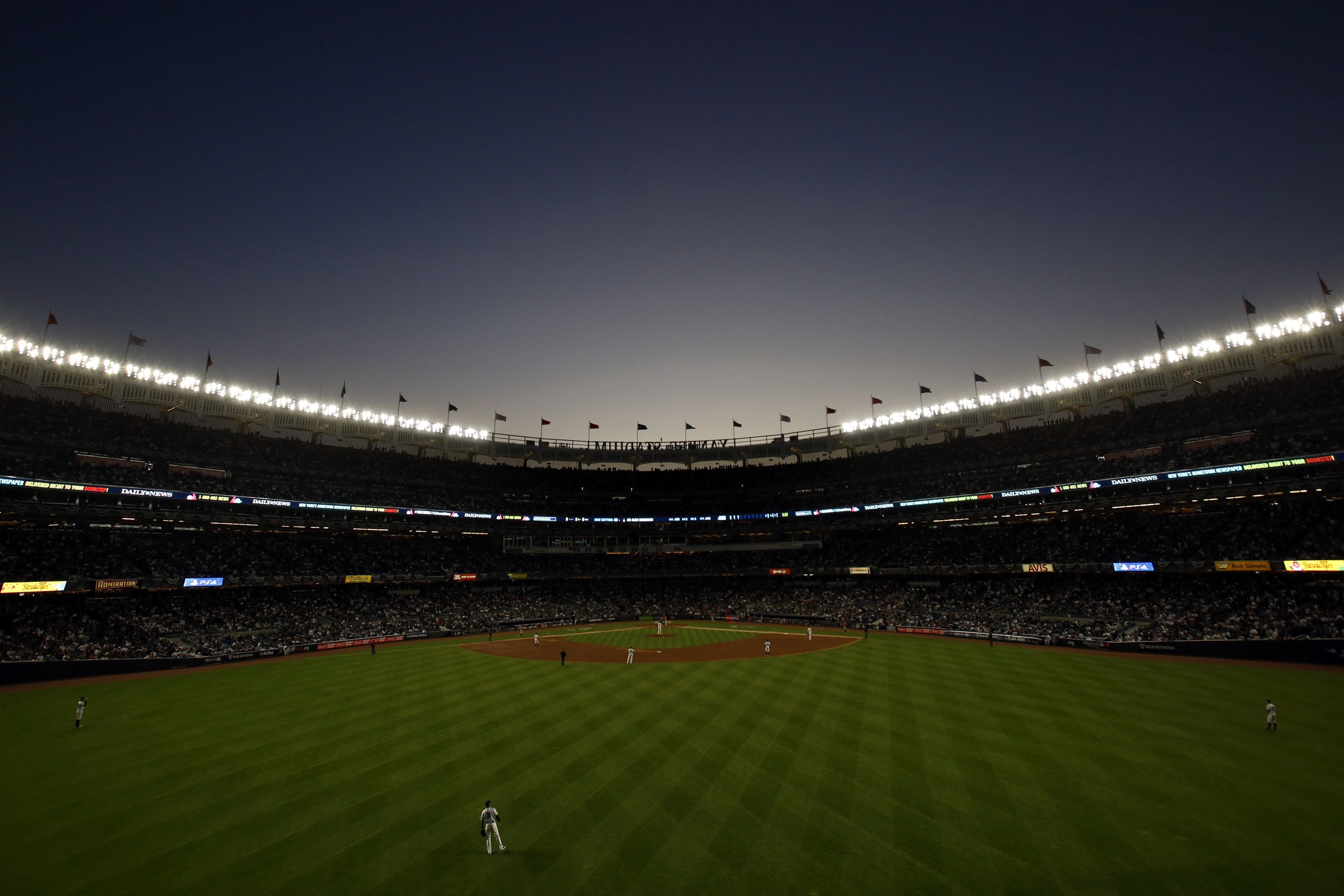

But if you scroll through the 1977 Blue Jays game logs, there is one strange line that sticks out. It is September 10th, 1977, a game played at Yankee stadium. The score, 19-3, makes sense if you assume that the Jays were on the losing end — the 1977 Jays gave up double-digit run totals 11 times over the course of the season. But it wasn’t the Yankees who scored 19 runs that day. No, it was the lowly Blue Jays who laid such an epic beating down. And not only did they beat the best team in the league, but they beat a future Hall of Famer in starting pitcher Catfish Hunter.

Big upsets happen in baseball, of course. Already this season we’ve seen the Miami Marlins beat Clayton Kershaw, which almost nobody would have predicted. But it is still fascinating that the worst team in the league could not only trounce the impending World Series champions so thoroughly, but hand them by far their worst loss of the season — their worst home loss, in fact, since 1923. I wanted to know just how that great Yankees team managed to put together such a spectacular display of ineptitude, and how that Jays team, who managed so little success in general that season, managed to appear, for that one afternoon, to be a heavy-hitting, complete-game-pitching juggernaut. There had to be reasons for this. There had to be people to hold responsible. A lot of things had to break the Jays’ way. Or maybe just three things.

JIM CLANCY

Nobody really thought Jim Clancy would make much of a mark with the Blue Jays in 1977. He was a 21-year-old with two full seasons in the minors under his belt, only one of which had been very good. He had control issues that needed to be worked out before he could become a viable major-league starter, even for an expansion team with little intention or hope of contending. He didn’t make the team out of spring training.

But veteran starter Bill Singer, having the worst season of his career, left his start on July 16th after two innings with a back injury. He would not return to the rotation that season, or indeed any other season: that start would end up being the last of his career. And to fill his spot in the rotation, the Jays decided to call upon the rookie Clancy. His first start would be at home against the Texas Rangers on July 26th. Going into the game, the Rangers were one of the hottest teams in baseball, having won 14 of their last 17 games. The Jays, meanwhile, had lost 16 out of their last 20. They hoped that the new face would perhaps provide some relief to their woes.

It was an unmitigated disaster. The Rangers won 14-0, setting a new franchise record for extra-base hits in a game with nine. Clancy pitched just two innings, allowing five earned runs on five hits and three walks, striking out just one. A flock of birds settled in the field, attempting to find food in the artificial grass, and were dispersed by a Texas double lined straight into their midst. “I haven’t seen anything like that in a long time,” Texas manager Bill Horton said of his team’s one-sided offensive performance.

This kind of welcome to the major leagues would typically bode poorly for a rookie, but the Jays, for lack of any better option, stuck with Clancy. In the long run, this turned out to be an okay move for the Jays: Clancy would go on to stay with the team for 11 more decent seasons. The rest of his 1977 season, though, would be characterized by wildly inconsistent performances. In his second start, the one immediately following his debut catastrophe, he pitched a complete game, allowing only two runs, one earned, on seven hits and just one walk; in his third start, he allowed five earned runs and walked five in under five innings. Clancy made 13 starts for the Jays in 1977 and recorded a decision in all of them, with a win-loss record of 4-9. All four wins were complete games.

So it went with Clancy in 1977: When he had it, he really had it, and when he didn’t, he really, really didn’t. The trick was that you never knew which Clancy you were going to get. And on September 10th, the Jays got the Clancy who had it. He pitched a complete game, allowing three runs on eight hits. He had a lot of bad days that season. This was a good one.

CATFISH HUNTER

Catfish Hunter started Opening Day for the Yankees in 1977. It was an obvious choice. Hunter was coming off five consecutive All-Star seasons, one of which featured a Cy Young Award. He was coming off ten consecutive seasons of 234 or more innings in a season. And, of course, he was the youngest pitcher in the modern era to throw a perfect game. Still relatively young at age 31, Hunter was the presumed staff ace for years to come.

Hunter won his Opening Day start, throwing seven shutout innings against the Milwaukee Brewers. But his 1977 season unfolded in a way that was far from the dominance that had long been expected of him. After that start on Opening Day, Hunter would not pitch again until May 5th; he pitched a complete game, but allowed five runs. His next start was even worse, with his defense stumbling behind him en route to a seven-run, 2 ⅓-inning catastrophe against the humble expansion Mariners. In his worst start of the season on June 17th, Hunter recorded only two outs while allowing four runs on four home runs to the Red Sox — an unthinkable outcome for a pitcher of his caliber and consistency.

The following season, Hunter would be diagnosed with diabetes during spring training, and arm issues began to plague him in earnest. But the evidence of his premature decline was already there in 1977. His 143 ⅓ innings pitched were his fewest since his rookie season, and his strikeout rate was the lowest of his career. The writing was on the wall.

And the decline was on full display on September 10th. After recording an out to start the game, Hunter gave up three consecutive hits — two doubles and a single — to put the Jays on top 2-0; after pitching around a single in the second, he gave up consecutive solo homers in the third to extend the Jays’ lead to 4-0. After opening the fourth with a walk, a groundout and an RBI single, Hunter was out of the game. His final line: 3 ⅓ innings pitched, seven hits, six earned runs — all allowed to an offense that averaged only 3.75 runs per game.

Hunter’s start accounted for just six of the 19 runs the Jays would eventually score, due to a combination of bad relief pitching and shaky defense on the Yankees’ part. If the Jays had faced Hunter perhaps even a season previous, this result would have been unconscionable.

ROY HOWELL

Roy Howell, though only 22 years old, was a disappointment to the Texas Rangers. Drafted fourth overall in 1972, he had yet to prove himself to be much more than an average hitter through two full seasons in the majors as the Rangers’ everyday third baseman. After starting the 1977 season 0-for-17, the Rangers felt that they’d seen enough. They traded him to the Jays in mid-May for Jim Mason and Steve Hargan — neither of whom were playing particularly well — in a deal that seemed very low-stakes for both parties involved. The change of scenery apparently did Howell a surprising amount of good: By the end of the month, his batting line had gone from .000/.105/.000 to .304/.378/.405.

Howell maintained a decent line through the rest of the season, hovering around the .280 mark for most of the summer. He was one of the Jays’ best hitters, certainly, but wouldn’t rank among the league’s best. His average began to climb back up towards .300 as September began, but the Jays simultaneously began one of the many headfirst slides that characterize a 54-win season. Going into the September 10th game, they had lost 12 out of their last 13, having scored only 14 runs in the entire month of September. It was not the optimal environment for any single player to have a breakout offensive performance.

But Howell, on that day, somehow put together one of the best single-game offensive performances in club history. After the game, he told reporters that the lingering hand injury had been bothering him so much that he had to make a conscious effort not to have an uppercut swing, for fear of causing himself even more pain. This makes his effort even more astonishing. In six plate appearances, Howell had two doubles, two home runs, and a single. He drove in nine of the Jays’ 19 runs and scored four, essentially forming a single-man wrecking crew. The combined efforts of five Yankee pitchers could only retire him once.

Howell himself seemed tickled by the absurdity of his good day. “Nine ribbies, that’s a month!” he said to reporters. In a single game, he had raised his batting average ten points.

1977 would end up being the best season of Howell’s career; though he was selected as an All-Star for a strong first half in 1978, he would never again put together such a solid performance and lost his everyday role in 1980. But his nine RBIs still stand as the Jays’ single-game franchise record — a memorable achievement in an otherwise unmemorable stretch of baseball.

So what is the moral of this story? There isn’t one, really. It was just an odd confluence of variables , a strange blip in an otherwise predictably unpleasant season for the Jays. That’s the thing about baseball, even when you’re watching a bad team. You never know how they might surprise you.

References

“Jays drop Ken Reynolds, 3 pitchers still to go.” The Globe and Mail, April 1, 1977.

“Mason, Hargan bring Jays Howell.” The Globe and Mail, May 10, 1977.

“Mets Get 5 in Ninth To Win, 7-2.” New York Times, September 11, 1977

Patton, Paul. “Rangers trouncing Jays’ worst, for now.” The Globe and Mail, July 27, 1977.

“Singer ponders surgery as Clancy makes debut.” The Globe and Mail, July 27, 1977.

“Yankees lose ground: Howell the hit man in Blue Jays’ assault.” The Globe and Mail, September 12, 1977.

Game logs from Retrosheet; player information from Baseball Reference

Nice memories of the Jays inaugural season. Talked to a Rangers fan recently about that Howell trade.