The fourth Collective Bargaining Agreement, signed between MLB Ownership and the Players Association on July 12, 1976, introduced the radical notion of free agency into baseball. It represented a monumental leap in the direction of players’ rights in a sport where, even to this day, their employment options are startlingly restricted. To wit: Players have little to no control over whom they are drafted by; can potentially be kept in the minor leagues as long as five seasons before potentially becoming available via the Rule 5 draft to another team they can’t select; and, once they finally reach the highest level, find themselves under control for three years at baseball’s equivalent of minimum wage, and for another three years after that at fractions of their true market worth.

If the length of team control wasn’t already challenging enough, even free agency has lost a lot of its luster in recent years as front offices have smartened up to the realities of the decline phase of a player’s career. Around the turn of this decade it became popular for teams to leverage those cost-controlled years into lengthy extensions at heavy discounts, forcing players to decide whether to bet on themselves remaining healthy and productive for each of the next five or six years, or to settle for an adequate lump sum of guaranteed cash today. In many cases the players have erred on the side of caution, locking themselves to an organization through their prime years only to find other teams unwilling to pay for their past production once they reach free agency around the age of 30.

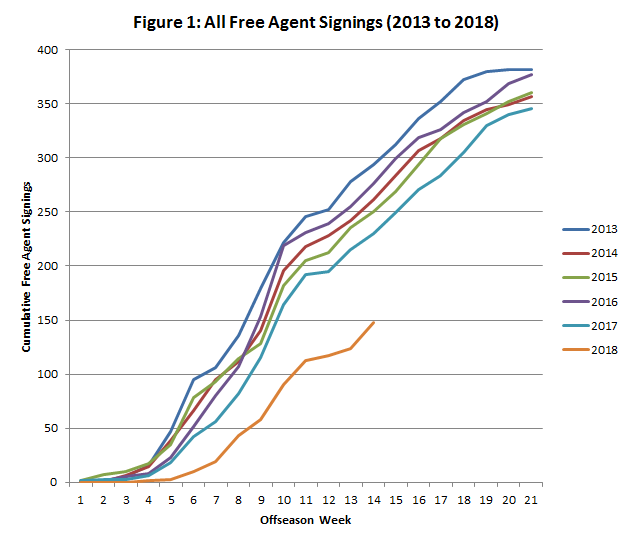

The growing trepidation with free agency has been fully realized this offseason, as signings are well below the last five years and have caused some to raise the possibility of price fixing or collusion. To compare signings across years, I broke down the offseason into 21 weeks, beginning with October 10th through October 16th and ending with February 27th through March 5th, at which point Spring Training has fully commenced. Figure 1 below was produced using these weekly buckets and the annual signing tracker available on Baseball Reference.

The 2013 offseason covers the signing period leading up to the 2013 season, and so and so forth through to 2018 (current). The data for 2013 to 2017 trends consistently, with 2017 potentially a foreboding sign of what was to come. The five-year average for free agent signings over the first 14 weeks of the offseason (ending January 15th) was 262. Here in 2018, we’ve seen just 148 free agents signed by January 15th, nearly 44 percent below that average. The previous five-year low by this date came in 2017 with 230 signings.

To hit the five-year average of 364 free agent signings by March 5th, we would need to average 4.4 signings per day from January 16th on, which is nearly triple that of the rate we’ve observed this offseason (1.5 per day).

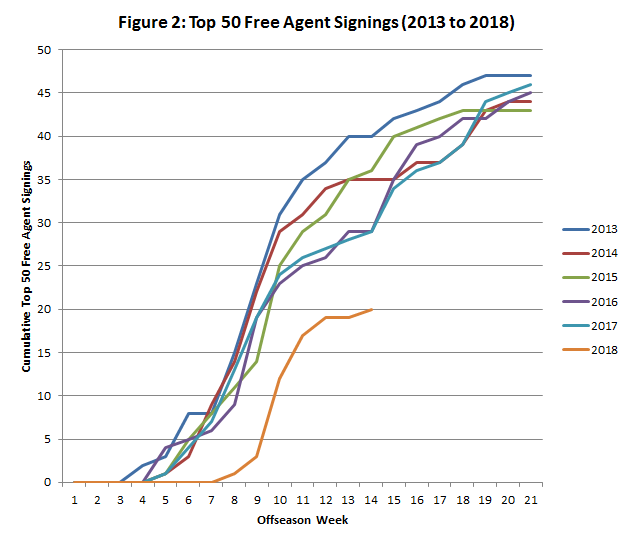

It’s not just the peripheral, mediocre, and older talent that have felt the cold shoulder from ownership this winter. The players widely considered to be the top of the class, i.e. those identified annually by MLB Trade Rumors as the Top 50 free agents, have suffered as much as the rest. Just 20 of the top 50 free agents for 2018 have signed as of January 15th, which is equally far below the five-year average of 34 by that date. Furthermore, most of those 20 were relievers who signed alarmingly well-scaling deals.

Just one of MLBTR’s top 11 has signed, and unsurprisingly, it’s a reliever: Wade Davis for three years and $52 million. The fifth-ranked potential free agent, Masahiro Tanaka, chose not to opt-out of the three years and $67 million remaining on his deal. And while many were skeptical of his decision at the time, in hindsight, you have to wonder if his agent, Casey Close, might have sensed that something was afoot. Yu Darvish, J.D. Martinez, Eric Hosmer, Jake Arrieta, Mike Moustakas, Lorenzo Cain, Lance Lynn, Greg Holland, and Alex Cobb all still find themselves without a home.

Over the last five years, the longest we’ve seen it take for two of MLBTR’s Top 10 free agents to sign was December 9th, 2017, when Dexter Fowler joined Yoenis Cespedes in having a deal. In 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016, it was November 29th, December 7th, November 18th, and December 4th, respectively. We’re six weeks past the previous worst and still waiting for someone on the above list to join Davis.

All of this is particularly noteworthy given the impending free agency of Josh Donaldson. Barring the unforeseen, Donaldson will be a member of inarguably the most impressive free agent class in recent memory. Among position players he’ll be joined at the top by Bryce Harper and Manny Machado, and not far behind that trio are Charlie Blackmon, Daniel Murphy, and Andrew McCutchen. On the pitching side, both Clayton Kershaw and David Price have the ability to opt out of their existing deals, and will be joined by the untethered Dallas Keuchel, Craig Kimbrel, Andrew Miller, and Zach Britton. That’s just the premium talent: The middle of the class is equally deep and unprecedentedly impressive, featuring Brian Dozier, Elvis Andrus, A.J. Pollock, D.J. LeMahieu, Gio Gonzalez, Patrick Corbin, and Cody Allen among many, many others. Seriously, just look at the list.

One could argue, and ownership certainly would were a collusion lawsuit to arise in the future, that teams are simply saving their money this offseason with their eyes (and chequebooks) set on next winter. But the current climate of penny-pinching and the depth of the class next winter could seriously hamper Donaldson’s ability to find the deal he seeks. He’s unequivocally among the most talented of his peers, but his 2019 age (33) will be working against him with Harper (26) and Machado (26) looking to push their way into the Alex Rodriguez and Giancarlo Stanton echelon of contracts. Donaldson is hyper-competitive and will want to play for a contender for the remainder of his career, but even the biggest spenders have a finite amount of money at their disposal in a given winter. If the Yankees, Dodgers, and friends splurge more than one billion dollars combined on Harper, Machado, and Kershaw, they might be hesitant to make a $100-150 million commitment to Donaldson as their second expenditure.

It’s why everyone, including both Donaldson and Mark Shapiro themselves, seems to realize that Toronto was, is, and continues to be his best fit. Even with his 2018 salary already settled, the suddenly tight purse strings across baseball and the continued unemployment of J.D. Martinez and Eric Hosmer in mid-January could serve as a catalyst to reignite discussions on a longer agreement. It would take some flexibility from the Rogers ownership group, particularly in the short term with Martin and Tulowitzki still under contract, but they can definitely make the dollars and years work on a fair and realistic contract.

Last week the Toronto Star’s Richard Griffin proposed the four-year, $110 million dollar contract signed by Yoenis Cespedes last winter as the framework for a Donaldson extension. With younger players struggling to find long-term deals now, and even younger players likely to command the attention next year, four years and an immense bucket of cash for Josh Donaldson today sounds like an excellent compromise.

Lead Photo © Nick Turchiaro-USA TODAY Sports

This offseason is weird, that’s undeniable. But there is no reason to suspect price-fixing, and Trueblood et al are irresponsible to do so.

It’s important to remember that collusion and competition are observationally equivalent, at least with respect to prices. Those well-scaling contracts? Not alarming at all; it’s much more likely that this is a result of healthy competition for these players’ services. Indeed, the fact that so many 7th and 8th inning guys are getting 2-3 years deals at $7-10M is probably evidence against collusion. The prices for these types of players has skyrocketed.

A simpler explanation:

a) the 2018-19 crop is amazing and teams plan on spending big.

b) The CBT incentivizes high-payroll teams to periodically reset their tax rate, especially in advance of high anticipated spending. Since teams were all subjected to the CBT at the same time, it makes sense that they are all resetting their tax rate at the same time.

It should also be noted that we have precisely one outlier off-season, and that not even complete yet. Way too early to draw conclusions.

Also, have any of these writers spouting off conspiracy theories about collusion taken even 5 minutes to think about how extremely difficult it would be for 30 teams to actually collude in 2018, and not be immediately found out?

If you haven’t read Passan’s piece, I’d strongly recommend that you do.

It hardly seems a given that JD would take a deal in the 4/$110M range. It seems reasonable enough, but why would a player who is so competitive by nature not feel to some degree that salary is another form of competition for him to try to win, whether via an extension or by testing the open market?

It’s not at all a given. He probably wants more. The whole premise of the article is that if he’s seeing comparable players struggling to find that kind of money this winter, and if he realizes that, at best he’ll be the 4th or 5th most desirable free agent next winter, it COULD be about as good as it’s gonna get. Or it might not be. We really don’t know. I think six months ago everyone was certain that he’d make bank in free agency, but what is happening this winter is unprecedented and groundbreaking, and it might be enough for him to reconsider.

I’m not sure I understand why the depth and size of the 2018-19 class should affect Donaldson’s earning potential? Can you explain.

Sure. Generally, any time there is significant increase in the supply of a commodity within a market, a surplus is created. With so many available and interchangeable options, economic surpluses lead to a decrease in the buyers’ willingness to pay, which subsequently leads to an expected decrease in price.

In the baseball landscape, free agents are those commodities. When so many very good free agents become available at once, the market becomes flooded. This issue is doubled down upon by the fact that, as Passan notes, at least 10 teams in baseball have removed themselves from free agency given the lack of incentive to win 75 games instead of 65.

Where 5 years ago you’d have 30 teams competing for the top 5-10 free agents, it’s now 20 teams. And because the 2019 class happens to be so deep, those 20 teams will be competing for the top 15-20 free agents. It becomes somewhat of an inverted dynamic. Where the elite bat once had 5 or 6 teams bidding for his services and raising his price, teams will now have low-ball offers out to 4 or 5 free agents at a given time. This gives them the ability to throw take-it-or-leave-it ultimatums around to see who blinks first. They may not get the first choice if another team overbids, but they can be reasonably confident they’re coming away with someone because there’s only so many seats available.

Hopefully that helps?

Ok, sure, but for every player that reaches free agency there is now a roster hole that needs to be filled. So supply and demand shift together, not independently, keeping the equilibrium price roughly the same. Lots of free agents => lots of needs; few free agents => few needs.

I think price might vary from year to year, but for other reasons, reasons that generate independent shifts in either supply or demand. These other factors, whatever they are, are probably more influential in years with small free agent classes.

This is a terrific out-of-the-box article. Thanks for writing it.

Hey K Shaw, it won’t let me reply to your comment directly so hopefully you’ll find my reply down here.

Hypothetically, yes. Every free agent creates an empty roster spot on their old team to be filled. That’s not reflective of reality, however, because those 10 teams not involving themselves in free agency are still releasing free agents into the pool. For example, if a team like Baltimore or Minnesota can’t re-sign Machado or Dozier, they’re not replacing that guy with a different expensive free agent. They’re going to replace them internally and for cheap with someone already in their system.

This imbalance is why we’ve seen the game shift towards younger players in the last five years as players in their mid-to-late 30’s can’t outproduce the difference in salary between them and the typical 0-3 guy.

Ok sure. But the “10 teams have removed themselves from free agency” effect is a separate issue; that would apply regardless of the size and depth of the free agent class.

My point is simply that–ceteris paribus–demand and supply shift together so there’s no reason to think there is a correlation between price and cohort size. Any fluctuation in a player’s earning potential from offseason to offseason must be due to other vagaries of the market.