One of my favorite parts of being a baseball fan is the sheer breadth of the history that can be learned, the staggering number of huge immortal moments and small, glittering fun facts that come with being a fan of any team. Even a relatively young team like the Jays has magic waiting to be discovered in its four-decade history, and it is a source of seemingly inexhaustible joy to burrow into this magic, reliving it through the pieces of it that remain—the fondly-recalled stories, the grainy video clips, the breathless newspaper headlines.

I realized recently that the very beginnings of the Blue Jays as a franchise were a significant gap in my knowledge.When I’ve looked into the team’s past it was usually into more successful years: the dominant teams of the 80s, the World Series champions of the 90s. The predictable but still-depressing struggles of an expansion team—carving out a space and an identity for itself, establishing a presence in a league, a sport, a city—were less interesting to me. I am not particularly disposed, I guess, to read about my team being terrible, especially when they aren’t any good right now.

But it didn’t take much digging for me to find out that my neglect of the Jays’ earliest games had caused me to completely overlook one of the team’s greatest moments. I had never heard about that first game in April 1977, the Zamboni on the field, the epic traffic jam, the crowds screaming because they wanted beer, screaming because it was snowing like hell and they were freezing out there in the bleachers, and then screaming because they won, their team had won, the team that hadn’t really been theirs before but was now. I had never heard about the two home runs in two at bats. I had never heard about Doug Ault.

***

Doug Ault loved baseball. This is the main thing I want you to know about him. He loved baseball first because it was the favorite sport of his older sister Brenda, the eldest child and primary caretaker in their troubled household. Seven years his senior, Brenda would spirit Doug away from their house to a local park, toting him on the back of her bike. They just played catch in the early days; as Doug got older and as his love of baseball grew, Brenda challenged him. She caught his pitching, shagged his fly balls, hit grounders at him to keep his glove sharp. When he began to play, she came to all his games; when he got down on himself, she encouraged him, reminded him of how talented he was.

Ault was talented. He was the star pitcher at his high school. He led his community college team from both sides of the ball, sending them to the National Junior College World Series. When he transferred to Texas Tech, he set a career batting record with a .418 average; in his senior year, his average was an absurd .475. For two summers in a row, he went straight from Texas to Alaska when the season ended, playing collegiate ball in Anchorage. He won a championship there, too.

He was undrafted out of college, though, which was perhaps surprising given all the success he’d had in his collegiate career. Maybe it was his limited defensive ability that made him an unattractive pick; maybe it was something about his swing that gave scouts pause, despite the gaudy numbers. He had, after all, displayed limited power up until his senior season.

Ault eventually signed as a free agent with the Texas Rangers. He spent four seasons in their system, his numbers getting better and better; in 1976 he played in nine games with the major league team in September, finishing with a .300 average in 21 plate appearances. The Rangers decided that they had better options at first base, leaving him unprotected in the upcoming expansion draft; the nascent Toronto Blue Jays selected him with the 32nd pick, far from guaranteeing him a spot in starting lineup.

Instead of being discouraged, Ault relished the opportunity to forge a new identity with this new team. “The odds are against me. I love it,” he said to a reporter at spring training. “To me it’s better if you have to compete and win the job.” Ault, at the time, had six other players competing for the starting role at first base. His odds weren’t very good. But he ended up on that brand-new team—batting third, no less. And in his very first at-bat, in the freezing snow on April 7, 1977, he became a legend.

***

Here is how my mind works when I do something good—when I achieve something that I am proud of. There is a brief rush of elation. I accept praise. I feel happy. Then I begin to search for reasons not to be happy, because if my performance was imperfect I am not allowed to feel good about it. (My performance is always imperfect. I am a human being.) From there, the self-hatred spirals. I am repulsed by my own pride, daring to feel good about an effort so flawed. It is clear, I reason, that I am some kind of horrible narcissist, inflating my own abilities in order to feel better about myself. I am a bad person. The voices of others telling me that I’ve done well become reminders that I don’t deserve any of it, that I am a charlatan fooling people into caring about me. And then, finally, a realization: this is the best thing I have ever done, the best thing that I will ever be able to do, and it is not nearly enough. It will never be enough.

***

Doug Ault was charismatic and cheerful. He was handsome, and he spoke well, and he had a nice voice. He was always smiling. Within weeks of that momentous first game he had an unofficial and unauthorized fan club out in the bleachers at Exhibition Stadium, a group consisting mostly of teenage girls, and when games were delayed due to weather (as they often were in those days) he would cross over from his position on the infield, stand by the fence and sign autographs. They loved him. They thought he was the best. But Ault was less taken in by his own good qualities. His propensity to get down on himself was exaggerated by the fame he was suddenly surrounded by, the expectations of greatness.

Ault batted .342 in April. The rest of the season was less forgiving. His poor defense at first base turned him into a liability, as he committed 16 errors over the course of the season; he finished with a slash line of .245/.310/.382. In the context of a 54-win expansion team in its first season, these numbers are far from unforgivable, but Ault wasn’t disposed to think of the context of the team. He thought of his failure to measure up to his own standards. For an entire decade, he’d been fantastic at baseball, if sometimes reluctant to believe it; he had worked hard, battled the doubt, found a place for himself on a new team in a new country, and immediately inscribed himself in that team’s history books. He had given thousands of fans the best day of their lives. But it wasn’t nearly enough. It could never be enough.

The ever-insightful Alison Gordon, in the chapter of her book Foul Balls! entitled “The Players,” had this to say about how baseball players react to failure: “For men not encouraged to define themselves by anything but their talents, failure can be emotionally devastating.” Ault was no exception to this. Every small mistake, every error or strikeout, weighed on his mind; the heavier he felt, the worse he performed, and thus the cycle continued. He lost his starting job in spring training of 1978. By the end of the season he was a third-stringer, on the bench most of the time, unable to even redeem himself on the field. “It’s been a tough year for me,” he told reporters. “I’d never been on the bench before and I let it bother me. It took me a long time to adjust.”

Others seemed to find his profession of internal hardship difficult to believe. After all, he was always so affable, so quick to smile. He was only two years removed from being Toronto’s golden hero, driving around town in a car with his name written on it. He had no right to be depressed. “Doug Ault is such a cheerful, easy-going guy,” reads the lede to the interview where he discusses his feelings of depression and inadequacy, “it’s hard to imagine him letting anything get him down.”

***

Here is another thing I want you to know about Doug Ault. In 1978, the Supreme Court ruled that MLB had to allow women reporters into the clubhouse. It was an earth-shaking move as far as the rights of women in sports journalism went. It was also, by and large, rather unpopular with the players. They were men, raised in the macho culture of athletics, and it was the 70s. So the misogyny that saturated the reporting and interviewing surrounding this event was unsurprising. A September 1978 Globe and Mail article about the first day women were allowed into the Yankees clubhouse opens with this line: “Women invaded the New York Yankee clubhouse last night but found no naked athletes.”

By my count, there are 11 players, managers and coaches interviewed in the piece, and almost every single one of them—even the ones who weren’t opposed to the opening of the clubhouse doors—had something demeaning to say. Yankees manager Bob Lemon said that “there were females in here, and I hope they were ladies.” Pitcher Ron Guidry, whose long-suffering shrug one can only imagine, said with an air of resignation: “They’re into everything else, they might as well come here.” Blue Jay Joe Coleman claimed that the only players who were in favor of opening the clubhouse to women were “the single guys on the team.”

There was only one solitary player who didn’t have any snide comments to make. When asked for his opinion, Doug Ault said this: “I met a few women sports writers in my time, and they were damn good.”

***

The Jays sent Ault down to triple-A Syracuse just after the end of the 1978 season. It was massive blow to him. He did his best to recover over the offseason. He played winter league ball in Venezuela, batting over .300 and leading the team to their first playoff appearance since 1968. Three weeks before the season was to start, he got married, too, hoping to bring the happy honeymoon vibes into spring training with the Chiefs. He was certain that he would be able to make the major league team again. He just had to stop pressing. He just had to stop letting the disappointment get to him.

But triple-A was even more of a struggle for Ault than being the forgotten man on the bench. He batted only .200 through the first three months of the season. His defensive waywardness led the Chiefs to move him out to a corner outfield position.

In June, Ault spoke to reporters candidly about how hard it was for him to be in the minors, how hard he was trying not to fail anymore, to live up to what he believed himself capable of. He was always brutally aware of what he was doing wrong, but the awareness of it seemed only to make the problem harder to fix. “My average stinks,” he said. “The worst thing you can do is press. That’s what I started doing here. I got to the point where I couldn’t have hit myself with the bat, much less a baseball.” It is a terrible feeling when the thing you love most in the world becomes your greatest source of anguish.

“We’re trying for a baby,” Ault told reporters when asked about his still-recent marriage. “But I’m finding that’s harder than I thought it would be, too.”

At an Italian restaurant far away from the Jays in Toronto or Ault in Syracuse, all the way down in Dunedin, they still had a poster up: a signed picture of Ault hitting that home run in 1977, framed in a place of honor.

***

I am about to say something that will sound extremely foolish to many of you, but here is my embarrassing truth: baseball is the best antidote to suicidal thoughts that I’ve ever had. I’ve been on ten different kinds of medications; I’ve worked out, relaxed, meditated, made music, done writing, talked to people, not talked to people, closed myself off from love and opened myself up to it. I’ve gone to work and I’ve gone to school and I’ve stopped going to work and I’ve stopped going to school. Nothing helped. Working out made me manic; relaxing made me bored and agitated. School and work felt pointless and draining; not being at school and work made me feel like a failure. Art hurts, and isolation is torturous. And when you connect with people, when you form mutually caring relationships, it is shockingly easy to believe that the right thing to do if you really love them is to rid them of the burden that you are and always will be. When you feel yourself to be nothing but a dark pit into which good things fall, it seems not just the right choice, but the morally imperative choice. The only choice. The only way to redeem yourself.

Baseball helps. I can’t articulate exactly why. It’s just always there when I need it. I don’t know what I would do if I felt like I didn’t have baseball anymore.

***

By the beginning of the 1980 season, Doug Ault was leaving his baseball fate in the hands of God. If God was willing, he told reporters, he would play for the Blue Jays again. If God was willing, it would surely happen. It was far from the confidence he had expressed in 1977, when all he had experienced was success, when baseball seemed fresh and exciting and full of possibilities.

Ault had once again gone to Venezuela over the winter, had once again put up fantastic numbers. While there, though, he had received some terrible news in quick succession. His wife’s grandmother was sick and was on the point of death. And his sister Brenda, who had given baseball to him, and who had recently been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis around when he had been sent down to Syracuse, was also gravely ill.

He left Venezuela. He went back to Texas, took a job at a construction site, and looked after his family. ”With God’s help, I’ll get back up there,” Ault said of his major-league aspirations. He had no such faith in himself.

“I really blew it mentally,” he told the reporters. This is something I noticed about Ault: he rarely spoke about his accomplishments, but talked at length and openly about his failures. “But I’ll be there. I’ll come as many years as they bring me.”

Ault played his last games in the major leagues in 1980. A spate of injuries led to his callup midseason; he played in 64 games, ten more than he had in 1978, but his performance was even worse than in that disappointing year. He slashed .194/.273/.306 in 161 plate appearances. The Jays released him at the end of the season.

***

Despite all of this, Ault was still at his happiest when he was on a diamond. He still wanted nothing more than to play and be successful. After the Jays released him, he took a contract in Japan, hoping to achieve some of the success that he’d experienced the first time he’d moved to a different country. He had a great season there, posting an average over .300. But he returned to North America after the season was over. There was something about the way his team in Japan was run that grated on him—that he felt was morally opposed to the spirit of baseball.

“It was the way they acted if somebody made an error,” he said. “The manager would come running out and pull the player off the field right there and then. They never did it to me, but I could see what it did to the morale of the team.”

His principles held, too, when he began the next season playing in Mexico. Ault led a large group of players on his team, the Tigers of Mexico City, in a mutiny against their manager, whose negative attitude Ault found repulsive. “He just couldn’t get along with anybody.”

A few weeks later, Ault had to leave Mexico, too: he got very sick, losing too much weight to continue playing. He returned to North America and decided to try his hand at managing. The Jays offered him a job as a playing coach in Syracuse. He expressed gratitude to the organization for extending him another opportunity, and he was particularly excited to work with a young shortstop named Tony Fernandez. “He’s the best prospect I’ve seen in ages.”

***

Ault had a gift for coaching and managing, for working with the insecurities of young players. He was given the job of managing the Jays’ high-A team in Kinston for two seasons before he was promoted to be the manager of Syracuse, the team on which he had spent such miserable years. The negative feelings didn’t seem to carry over. He led the team to a championship in his first season in 1985, winning a Manager of the Year award.

In an article from the middle of that championship season, Ault talks about the difficulties in motivating players at the triple-A level—both the ones on their way down, bitter and trying desperately to remain in professional baseball, and the ones on their way up, who find themselves blocked from the major-league team despite exceptional performances. “You just hope they have respect for you that they’ll play hard just the same.” It was what Ault expected of himself, too: he found himself “in the same boat,” blocked from a major-league managing position by the utterly immovable Bobby Cox. The players Ault worked with on that team included a frustrated, incredibly talented young reliever by the name of Tom Henke, who was almost ready to leave the Jays organization entirely.

***

Ault never realized his dream of managing the big-league Jays. After his second season with Syracuse, in which the team finished below .500, he was reassigned to manage the Dunedin Jays. The front office said that they believed he worked better with younger players; Ault viewed it as a demotion, another frustrating step backwards. Still, he stayed with the organization. He stayed through yet another demotion, down to low-A St. Catharines, where he worked with the only all-women front office in baseball history. He even accepted an assignment to manage the Jays’ affiliate team in Australia in 1992.

By this point, Ault’s frustration with his situation was becoming more pronounced. Before going to Australia, he went through a painful divorce; while in Australia, he was fined $6,000 for refusing to take the field one day. The field conditions, he said, muddied and slippery, were too dangerous. He could not allow his players, in good conscience, to take the field and risk injury.

The Jays did not take such a noble view of the situation. Upon Ault’s return to North America, he was demoted yet again, this time to the GCL. And at the end of the 1994 season, he was fired. It was the last job he would ever hold in the organization. “I wouldn’t call it mutual but he understood what we were doing,” said then-GM Gord Ash.

Ault, for his part, said this of the Jays: “I don’t care if they came in and beat me with a club. I’d never say anything bad about them.”

***

Doug Ault, for all the sorrow that he’d experienced during his tenure with the Jays, loved the team, the fans, the organization. He became a fixture at alumni events. He threw out first pitches, appeared at fundraisers, showed up in Dunedin to watch spring training games, all decked out in Jays gear. He was still charming, still had the easy smile. He got married again. He went into car sales. The legend of April 7, 1977 became ever more distant, until there were adult Jays fans who hadn’t been alive to witness it.

Doug Ault loved the Jays because the Jays had loved him. Whenever he was interviewed, so much less frequently than he once was, it was the love he would talk about, the happiness he’d had in those good years, the sound of cheers shaking Exhibition Stadium, the clapping from a million numbing fingers, the snow falling on 44,000 heads. “Standing in the outfield, in a blizzard, amid 46,000 freezing fans,” he said in 2001, in that warm, engaging voice of his, “I thought, these have to be the best fans in baseball.”

***

Doug Ault committed suicide in 2004. This is the first thing you will find out about him if you search his name on Google. You will find countless obituaries and post-mortems, documenting his “rise and fall.” That was the narrative that circulated in 2004. I am not going to write about any of that. I think they are wrong. I think they are missing the point.

There is a really strange thing that the public does when they think about suicide victims. I think it’s a kind of lack of understanding of what life is like when you feel like the only right choice is to stop being alive. People act like there was a time when it was easy, and then, all of a sudden, it was hard, too hard to handle. Sliding from the top of the mountain to the bottom until you hit the ground. Thud. The end. How tragic.

People don’t realize that the tragedy of suicide is not a tragedy of descent. The ending is tragic, but the life is not: the life, however long it was, is a shining document of victory. Every day lived a marvelous, impossible transcendence of hope over despair. I read Doug Ault’s interviews, every single one of them that I could find, dozens upon dozens, and every word he said about how he felt like a failure, how he got down on himself, was achingly familiar. I marveled at how he was able to achieve all that he did. Because I put myself into a coma at 17, having done absolutely nothing, and I only survived due to sheer luck. Doug Ault knew the darkness, and he lived to age 54. He had become one of the best people in the world at his chosen skill. He had helped hundreds of others master it. He was a kind, easy-going person. He loved his family, and he loved baseball.

Doug Ault’s life was not a tragedy. It was not a rise and fall. It was a life in which joy triumphed, day after day after day, until the one day that it didn’t.

***

Even though this first game and the legends that surround it are familiar to me by now, I still can’t believe how wonderful it all is, how utterly perfect. Perfect that a baseball team based in Toronto would play its first game in a snowstorm. That the bleachers at Exhibition Stadium were packed with people shouting for beer, who mistook tape rolls in pockets for hockey pucks. That the first two Jays batters ever struck out, barely able to grip their bats with cold, and that with two out and nobody on, boos raining down from the disappointed and cold-fingered masses, with the tension rising and the pillars of the stadium shaking with the noise of expectation, a 26-year-old rookie, a no-name nobody, sent a pitch into the left-field seats. The Blue Jays had their first hit, their first home run, their first hero. He homered again, in his second at-bat, and the Jays won 9-5. The fans went home happy, already bonded to the team by this shared unforgettable experience. When they thought about the Blue Jays, no matter how many years in the future, they would eventually come back to this.

Ault beams as he narrates the story of that day, and though he remembers the fame that came after with some smiling self-deprecation, you can see the pride and elation that still came with the remembrance of that day when everything just worked out so beautifully.

I watched this video on a dull, ugly, baseball-less January day over forty years after the fact, a day where I once again became overwhelmed by that pull toward nothingness. It made me happy, too. Even though I wasn’t even close to being there. Even though I’ve never been to Toronto, even though the only connection between those Jays and the ones I have loved is a name, a logo, a mirage of continuity. It’s that magical quality of loving baseball—the nonsensical immediacy of a joy shared long ago, by a baseball player you never knew.

I am grateful. I am so grateful that Doug Ault shared this joy with me.

***

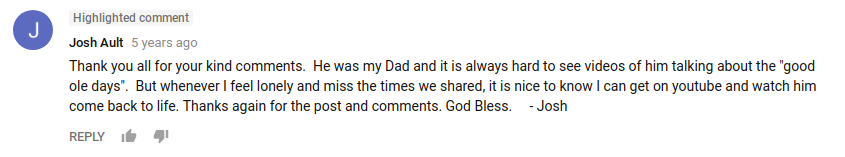

There is a comment on the video from a user named Josh Ault, left in 2013, nine years after Doug Ault’s death.

Lead Photo: Jason Getz-USA TODAY Sports

References

Abel, Allen. “Jays’ first hero hopes to return.” Globe and Mail (Toronto), March 21, 1980.

Aitken, Kathi. “Blue Jays caravan pulls into town.” Spectator (Hamilton), February 17th, 2001.

Byers, Jim. “Ault, Jays part on friendly terms.” The Record (Kitchener), September 28, 1994.

Campbell, Neil. “Slugger’s friends say he wants to come back: Jays block A’s bid to sell Carty.” Globe and Mail, September 1, 1978.

Davidson, James. “Jay hopefuls losing patience.” Globe and Mail, June 8, 1985.

“Doug Ault.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/a/aultdo01.shtml (accessed January 8, 2018)

Elderkin, Phil. “Land of the Rising Sun — and rising baseball ability.” Christian Science Monitor (Boston), March 23, 1981.

Gordon, Alison. Foul Balls: Five Years in the American League. Toronto: Mclelland and Stewart, 1984.

Hickey, Trisha. “25th Blue Jays luncheon: Carlos and the boys boost annual Variety fundraiser.” National Post (Don Mills), June 16, 2001.

“Jays assign Ault, Iorg to Syracuse.”Globe and Mail, November 16, 1978.

“Jays’ opening day hero fined $6,000 in Aussie league.”Kitchener-Waterloo Record, December 9, 1992.

“My average stinks, says .200 Ault.” Globe and Mail, June 30, 1979.

Patton, Paul. “Ault is happiest when playing ball.” Globe and Mail, June 29, 1982.

Patton, Paul. “Chiefs await the call of Blue Jay big time.”Globe and Mail, August 10, 1983.

Patton, Paul. “The insider’s baseball: Tribe’s Cruz has hefty problem.” Globe and Mail, March 17, 1979.

Patton, Paul. “Minors no fun for star of ’77 opener.” Globe and Mail, March 29, 1979.

“Players make best of it: Women in Yank clubhouse but only Yogi fled for safety.” Globe and Mail, September 27, 1978.

Skelton, David E. “Doug Ault.” Society for American Baseball Research. http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/9e0451ed (accessed January 8, 2017)

Smith, Veranda. “Doug Ault is enthusiastic about fighting for a job on the Blue Jays.” St. Petersburg Times, March 15, 1977.

As somebody who is a writer in an unrelated field, this is the best piece of writing I have seen in a long, long time. Thank you Rachael for bringing this story to life.

this is beautiful.

A fine, moving piece. As a long-time writer and editor whose skills are primarily on the technical side, I can say with complete certainty that the “possessing no useful skills to speak of” part of your bio blurb is very, very inaccurate.

This is so wonderful. Thank you.

:’)

Beautiful

This is magnificent. You’re magnificent. Thank you.

I really enjoyed this, Rachel. Thank you for sharing it.

Dammit, I’m sorry. Rachael. Rachael. Apologies.

jesus tapdancing christ rachael this was unbelievable you are a luminary

Such a beautiful story and so incredibly well written. It’s both heartbreaking and joyful to read. Well done. So very well done.

You are the writer I look for when I open this site, and I’m always grateful to see your by-line. I hope you can feel genuinely good about all this praise, even though you’ve described how hard that is for you. I look forward to the next one.

This is the best article I have read on any subject in a long time.

Thank you

Thanks.

Thank you for writing so beautifully and personally about what too many must manage each and every day. And I agree; baseball and all its factoids is a haven for so many storms.

I was 8 rows up in the left-field bleechers on that snowy April day when Doug Ault hit the first homer. We did go crazy and I remember none of us cared about the ball as it bounced around. We cared about baseball and being there at the game. Doug Ault will alwasy be remembered and now more so because of your thoughtful piece on sports, life, and how to deal with the hard knocks we all get in this crazy game called life. Un abrazo fuerte.

Reading a wonderful piece such as this is always a bright spot in my day. I can’t explain why either, but I feel the same way about baseball that Rachael does. May it always be there when we need it most.