The conventions of sabermetric analysis are a funny thing. In theory, they should be agile and flexible; those following them should willing to adapt to new data findings. However, in practice that’s not always the case. Just as old-school baseball fans believe in closer mentalities and clutch performances, new school fans have DIPS theory and a standard aging curve. One of those two pairs is grounded in a bit more data than the other, but both cases are subject to outliers that won’t perfectly fit the model. Marco Estrada is one of those outliers and my personal bias towards the norms of DIPS created a reluctance to accept his success.

*****

Marco Estrada breaks every rule of thumb for pitching success. In theory, the best pitcher is tall, throws hard, gets a lot of ground balls, and doesn’t give up a lot of home runs.

Estrada isn’t overly tall—at barely 6′, you wouldn’t be able to spot him out in a crowd. Estrada doesn’t throw very hard—his average fastball velocity was fifth lowest among qualified starters in 2016. Estrada doesn’t get many ground balls—his 33.5 percent ground ball rate was the third lowest in baseball. Estrada gives up a lot of home runs—1.19 per nine innings was the 16th worst mark in the majors.

Yet in 357 innings over the last two seasons, Marco Estrada has pitched to a 3.30 ERA, which is 18th best across MLB. There’s only five other Blue Jays pitchers who’ve matched or beat that two season ERA: Roy Halladay, Dave Stieb, Doyle Alexander, Jimmy Key, and Roger Clemens. That’s good company.

In other words, he has to be doing something right.

Over the last two seasons, a number of analysts, including BP Toronto’s own Joshua Howsam, have tackled the subject of Marco Estrada’s success. Their conclusion? Estrada pitches in a way that allows him to induce weak contact and maintain a BABIP below the standard .300. The analysis was sound, the arguments were logical, but they subvert the conventions of standard sabermetric analysis. The main tenant of defensive independent pitching (DIPS) statistics like FIP is that pitchers have little control over the type of contact that is made off of them and that they can only control the true outcomes: strikeouts, walks, and home runs.

Through one season, Marco Estrada’s success could be thrown away as a fluke. His 2015 BABIP of .216 was the lowest mark since Jeff Robinson’s 1988 season for the Tigers in which he pitched to a 2.98 ERA. Robinson pitched in parts of five other seasons in the major leagues and he never again finished a season with an ERA below 4.50.

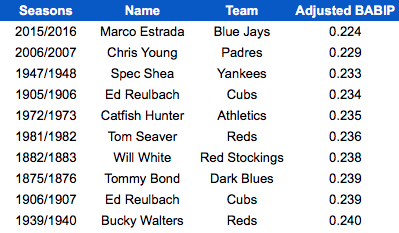

Through two seasons, Marco Estrada’s success has to be seen as a trend. His combined BABIP between 2015 and 2016 is .224. When you adjust for era, Estrada’s two season BABIP is the lowest in major league history.

That’s an extreme statistical outlier; perhaps the most prominent in the history of baseball. However, if a statistical outlier is recorded over a larger sample, the idea that there’s more to it than luck is further affirmed.

All that said, when the model for success is well established, wrapping one’s head around anything or anyone that bucks the trend can be tough. As a result, a comment such as this one, taken from a piece on Marco Estrada’s changes, seems like the rational point of view:

“That he is pitching differently than he has in the past doesn’t excuse the awful DIPS numbers. Estrada has the worst xFIP- in the AL among qualifiers, and he doesn’t have a history of suppressing HR/FB (the opposite, in fact). If he continues to not strike out that many guys and give up a ton of fly balls, he will get hurt.”

While I didn’t write the comment, one of myself or the many other dismissers of Estrada’s early success easily could have. It’s rational reasoning backed by a mathematical model, which is the best way to logically tackle a problem, but it doesn’t always end with the correct answer. Outliers exist.

*****

We shouldn’t dismiss outliers, but we also shouldn’t not dismiss them. We need to be skeptical of results, but more open to explanations for them if they’re backed by new data.

In Estrada’s case, there’s still likely some luck involved in creating the lowest two season BABIP in the history of baseball, but luck alone is not that effective. However, that doesn’t mean reverting to the idea that the gritty ballplayer can succeed on hard work alone, as that’s rarely (if ever) the case. A player has to be exceptional in some area, even if that area isn’t standard in our evaluation. As newer data has shown, Marco Estrada is exceptional at spinning a baseball. That skill doesn’t fit in to our existing rules of thumb for pitching success, but it should add a thumb to this proverbial hand.

Conventions exist for a reason and you can look no further than the top of any MLB pitching leaderboard to see why. You’ll find names the names of tall, fire throwing, and strikeout getting pitchers like Clayton Kershaw, Noah Syndergaard, and Justin Verlander. But conventions are only the normal way of doing things. By definition they’re made to be broken. As statistically inclined fans, we need to do a better job of recognizing when that’s the case.

Lead Photo: © Butch Dill-USA TODAY Sports

Also of note is that Estrada’s flyball numbers are misleading because more of them than normal are infield popups, not warning track outs.