Marcus Stroman has pitched parts of three seasons in his major league career, and one of the more interesting peculiarities to develop is his worse-than-expected run prevention ability. The fielding-independent metrics love him: over those three seasons, his 3.36 FIP ranks 25th among 127 starting pitchers to throw at least 300 innings, while his xFIP places a better-yet 19th. Conversely, his ERA of 3.97 ranks 73rd, and his ERA-FIP split of +0.61 is ninth-worst on that list. The greatest culprit is Stroman’s strand rate of just 69.4 percent, which ranks as the 13th worst and is well below the league average of 73 percent.

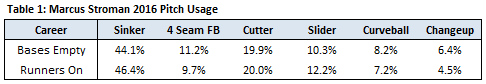

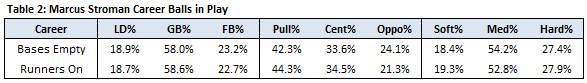

Pitching from the windup with the bases empty, Stroman has been a revelation. Opposing batters have hit just .231/.277/.345 over 839 plate appearances against him, due largely to his exemplary ability to keep the ball on the ground. With runners on, however, they’ve thrashed Stroman to the tune of a .294/.340/.454 slash line over 548 plate appearances. The first question is – what the heck is he doing differently? Tables 1 and 2 below show Stroman’s 2016 pitch usage (via MLB Savant) and career batted ball profiles (via Fangraphs) in bases empty versus runners on situations, leading one to believe, well, he’s not doing anything differently at all.

Stroman’s pitch usage in the two circumstances is nearly identical. In fact, one could observe that he’s relying more heavily on his two best pitches – the sinker and slider – in runners on situations, which should augment his numbers if anything, not crater them in the opposite direction. The batted ball profiles hum a similar tone; the type, direction, and strength of contact are basically the same across the board. Yet, despite attacking batters with largely the same approach and generating an array of batted balls with only trivial differences, his batting average on balls in play (BABIP) skyrockets from .277 to .350 from one circumstance to the next.

Typically, the granularity of macro level batted ball data is enough to accurately explain a premise; however, in this case, we need to delve to the micro level to have a better understanding of why Stroman’s BABIP has increased by seventy-three points despite indistinguishable profiles. In order to do so, I compared Stroman’s BABIP by batted ball type in each situation to the league average.

The league batting averages on line drives, groundballs, and fly balls are .685, .239, and .207, respectively. In both bases empty (.696) and runners on (.707) situations, Stroman’s line drive outcomes mimic the league average within reasonable margins, suggesting they’re not the culprit behind his baserunner demise. Fly balls make things a little more interesting, as his opposing average on balls in the air declines from 54 points better than average (.153) to just 9 points (.198). With that being said, this 45 point decline doesn’t nearly account for the 73 point worsening with all batted balls, particularly when considering how seldom Stroman actually surrenders fly balls.

As is often the case with Stroman, the answer can be found within his groundballs. With the bases empty, Stroman has limited opposing batters to a .184 average on groundballs; 55 points better than average. The moment runners get on base, however, batters at the plate have run a .286 average on groundballs – a remarkable 102 point swing in the wrong direction. We’ve reached the point in Stroman’s career where the phenomenon can’t simply be waved away with sample size disclaimers or chalked up to bad luck, especially when the splits have yet to show any sign of regressing towards the mean. Stroman has been slaughtered by groundballs with runners on, leading to the second question – why?

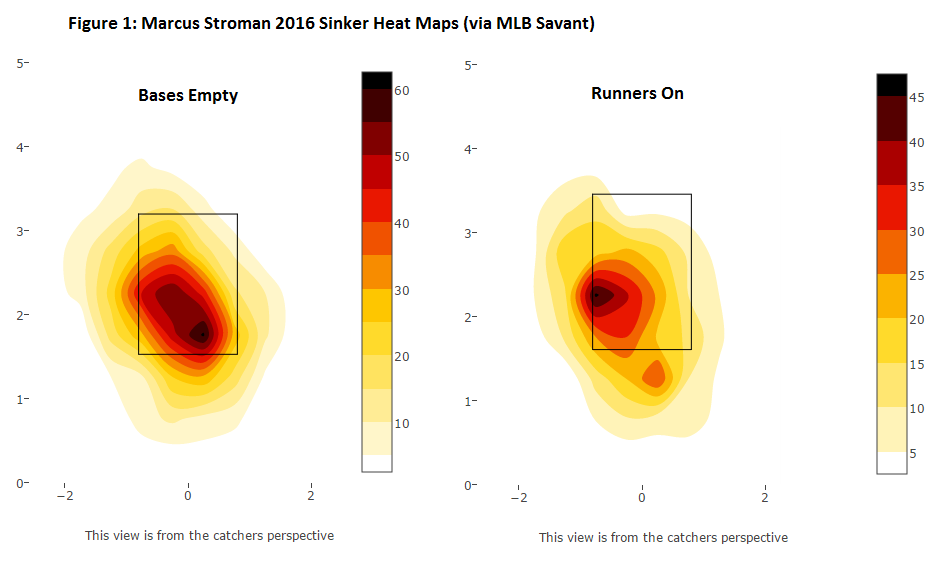

The heat maps above, from MLB Savant, depict the location of Marcus Stroman’s sinker with the bases empty versus runners on here in 2016. The horizontal focal point has shifted, but what’s most apparent to me is the elevation change once Stroman begins to pitch from the stretch. The cause may be that he is struggling to stay on top of the ball, or maybe he’s trying to catch more of the plate in order to better induce a ground ball for a double play, but the result is that the central cluster has climbed from roughly 1.8 feet above ground to 2.3 feet.

“Groundball” is a loose term used to describe any batted ball with a launch angle of +10 degrees or lower, but obviously there’s a sizable difference between a sharp groundball with a launch angle of +5 degrees and a chopper off the dirt in the batters box with a launch angle of -20 degrees – differences that simply aren’t picked up when evaluating all groundballs as a single and homogeneous entity. Given that we know Stroman’s groundballs have statistically done more damage with runners on, and that his sinker has been elevated with runners on, perhaps launch angle is the basis for his struggles.

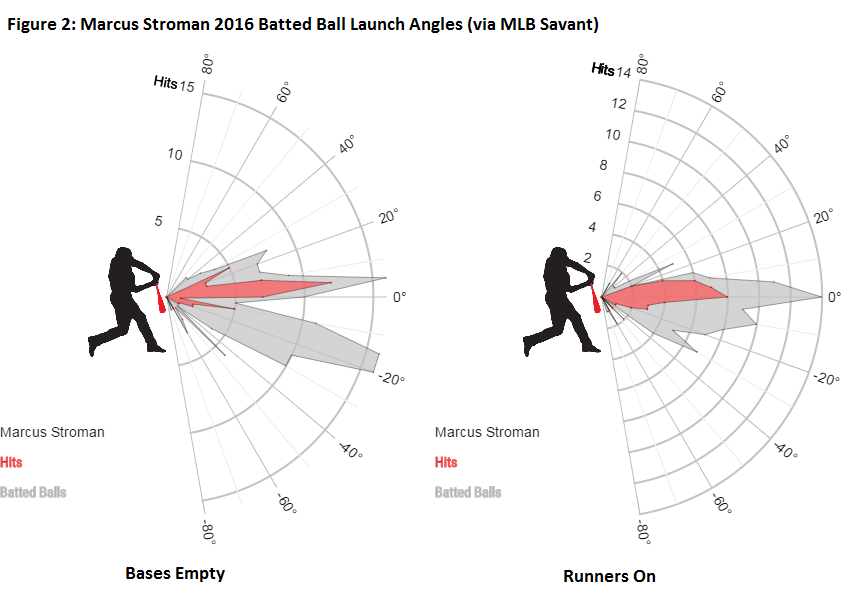

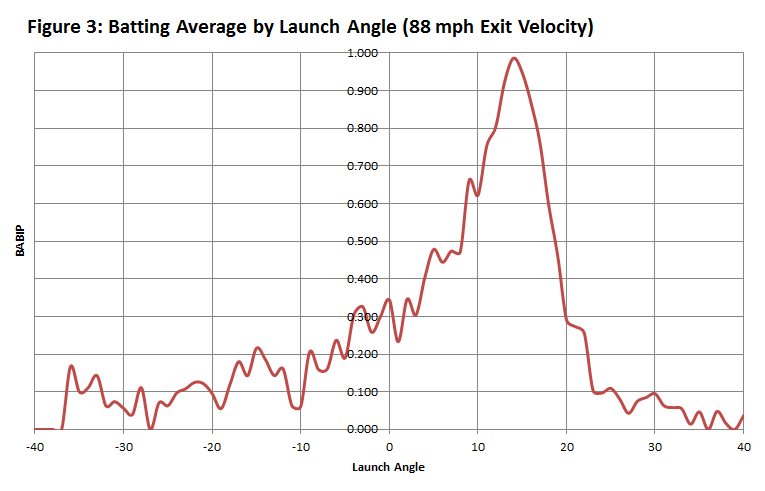

It’s not conclusive beyond a reasonable doubt, but it’s certainly moving in that direction. Stroman has been able to induce a ton of infield choppers (clustered around a launch angle of -20 degrees) with the bases empty, essentially all of which have turned into outs. With runners on, that cluster of choppers has evaporated, instead filling up the +10 to -10 degree window which contains a much greater probability of base hits. Via Statcast, figure 3 below shows the batting average by launch angle for the 4,314 batted balls hit this season between -40 and +40 degrees with a league average exit velocity of 88 miles per hour.

The line drive danger zone of +11 to +25 degrees sticks out like a sore thumb, but pitchers are still getting rocked on batted balls from -5 to +10 degrees, too – all of which are classified as groundballs in the Statcast era. Of those sixteen launch angles, only one (-5) has resulted in a batting average below .200, and just three (-5, -2, +1) have resulted in batting averages below .300. Breaking things out further (and, admittedly, arbitrarily), 402 of 1,033 ground balls hit with a launch angle of -5 to +10 turned into base hits – a .389 average; whereas just 145 of 1,177 hit with a launch angle of -6 to -40 degrees turned in hits – a .123 average.

While Stroman has maintained an excellent 58 percent groundball rate across the board, the above very clearly reinforces something that most baseball fans always assumed: not all groundballs are created equal. For whatever reason, when runners get on base, Stroman hasn’t been able to get his sinker down quite far enough under the swing plane of opposing batters, and they’ve hit sharp grounders ripping across the infield turf rather than easy bouncers at his quartet of capable defenders. Most sports have adopted the “game of inches” moniker, but this tagline is never truer than with baseball where a round ball is being struck with a cylindrical bat. An inch or two can be the difference between a sharp base hit and an easy ground out, and unfortunately, Stroman has been getting too many of the former when he’s in dire need of the latter.

Without knowing the reason why the sinker is getting elevated the extra few inches it’s impossible to know how to fix it, or whether it’s even fixable at all. The easiest explanation would be that Stroman is doing it intentionally in order to try to end a potential threat on one pitch, which could be resolved by simply pitching further down in the zone and accepting that you’re going to surrender a few more walks in doing so. Infielders can’t defend the base on balls, it’s true; but the data suggests they can’t defend a barrage of squared-up groundballs either, and when push comes to shove, at least a walk won’t score a guy from second base. If Stroman wants to improve his run prevention with men on base, the key may be to pitch less aggressively, getting his sinker moving down and out of the strike zone.

All data effective as of September 9th.

Lead Photo: John E. Sokolowski-USA TODAY Sports