It’s been a bit of a whirlwind half season for Marco Estrada. He started the year on the disabled list with back issues, returned to the rotation in mid April, ran off a record-breaking streak, was named to the All-Star game…and now finds himself back on the DL with back issues. Despite the stretches of unfortunate injuries, ever since joining the Blue Jays rotation in May 2015, Marco Estrada has been the best, most consistent starter on the staff.

Last year I wrote a piece breaking down how Marco Estrada was using his “rising” fastball up in the zone to complement his curveball and world-beating changeup. However, much of that work was done with Dioner Navarro as his personal catcher. As such, I vowed to compare Navarro’s game-calling with Martin’s at various points in the season. I first checked in back on May 10, and found that Martin had completely altered the approach, going away from the 2015 approach of throwing everything at the top of the zone. With a bit larger sample now, it’s time to once again delve into the Martin-Estrada combination and see just how this man is getting outs with an 89 mph fastball.

*Of note, I am going to be omitting information from Estrada’s lone July start, against the Indians, because he was clearly hurt during the outing, having lost 3 mph on his fastball and almost completely unable to bend over.

With that bit of housekeeping out of the way, let’s dive in.

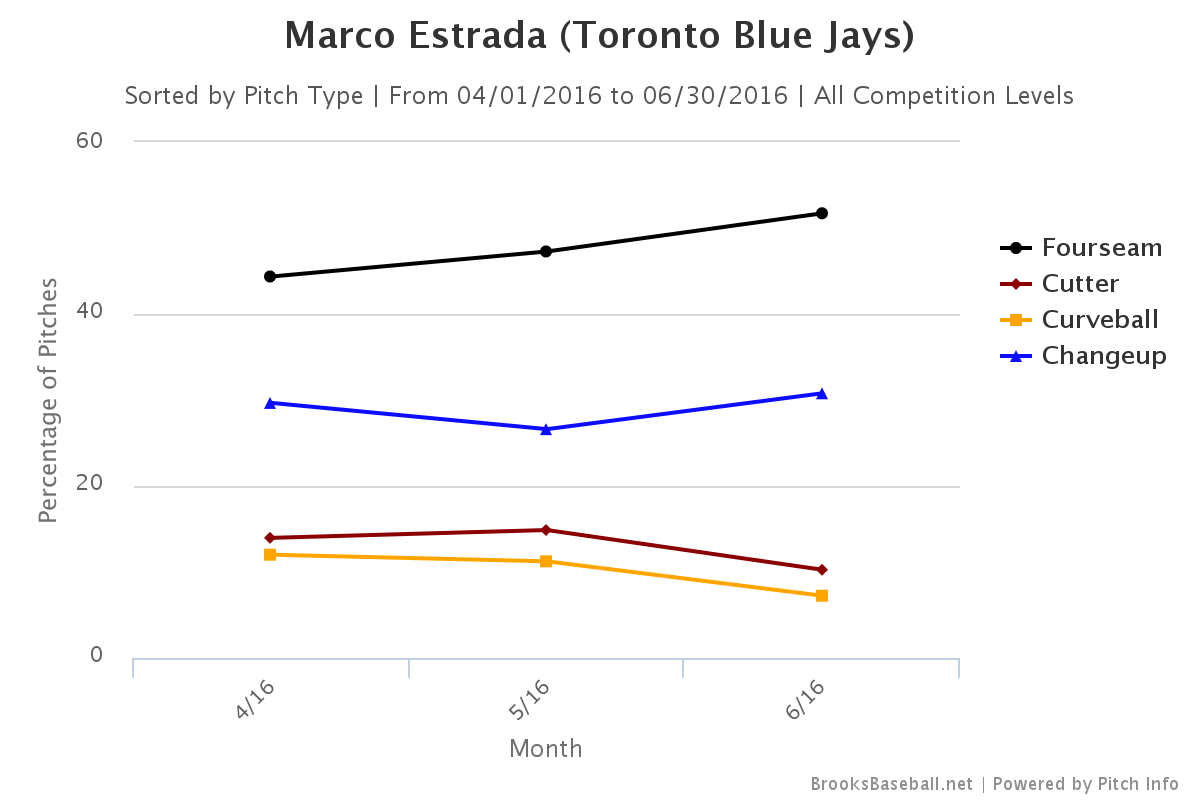

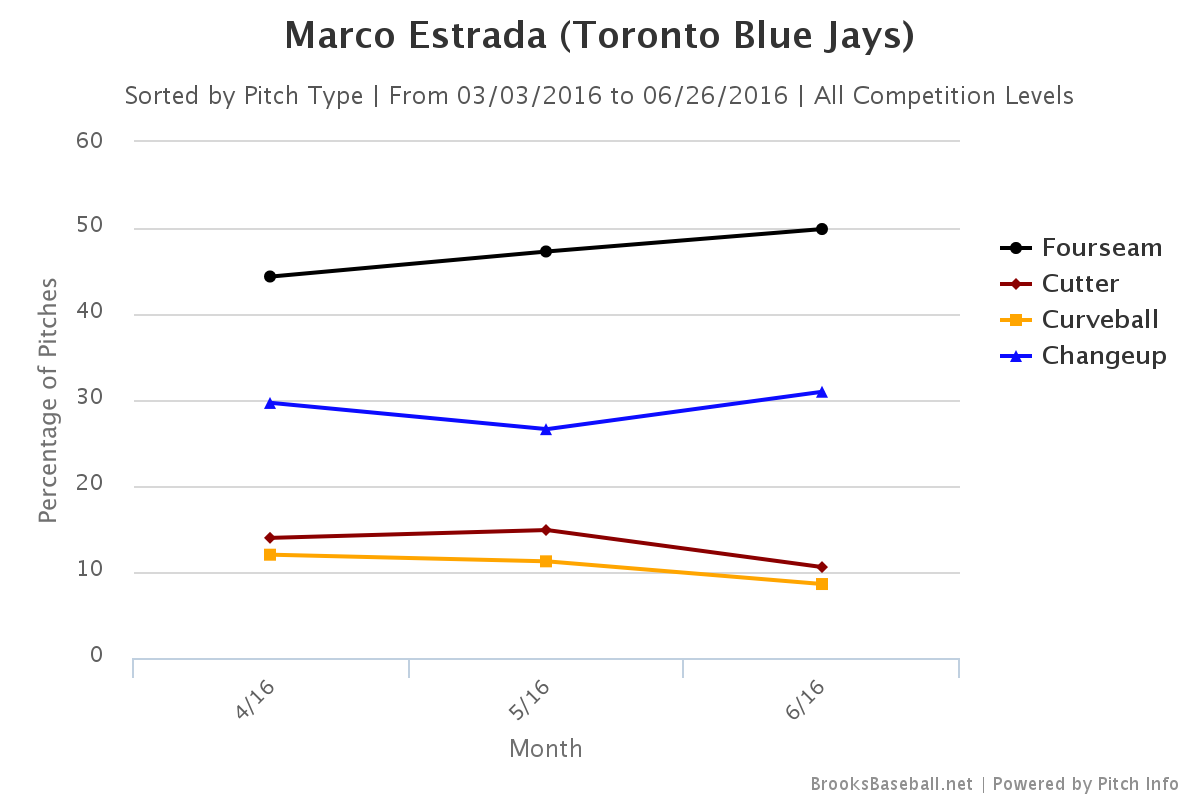

At first glance, it appears that Estrada has become increasingly reliant on the fastball and changeup, with the curveball usage falling to just 7.2 percent in June. However, that includes a start in Colorado where Estrada threw just one curveball, a clear outlier. The reason is simple enough: the ball doesn’t fall there. Even if we pull that start out of the equation, we still get a rise in fastball-changeup usage and a reduction in the other two offerings:

Somewhat surprisingly, the reduction in use of the curveball has led to its most tough to hit month yet. He is getting only slightly more movement (7.6” of drop compared to 7.4”), but the swing and whiff rate has jumped from two percent on curves in April, to 8.8 percent in May, all the way up to 22.9 percent in June. One assumption could be that hitters are no longer expecting the pitch, and thus having trouble making contact, but the pitch has also seen its groundball rate drop from 57 percent to just 20 percent. Really, it just seems like some small sample size noise. After all, as mentioned previously, the curve/cutter are being thrown less and less, so their analytical value is limited. 80 percent of Estrada’s offerings are now either fourseam fastballs or changeups, so that’s where I’m going to shift the focus.

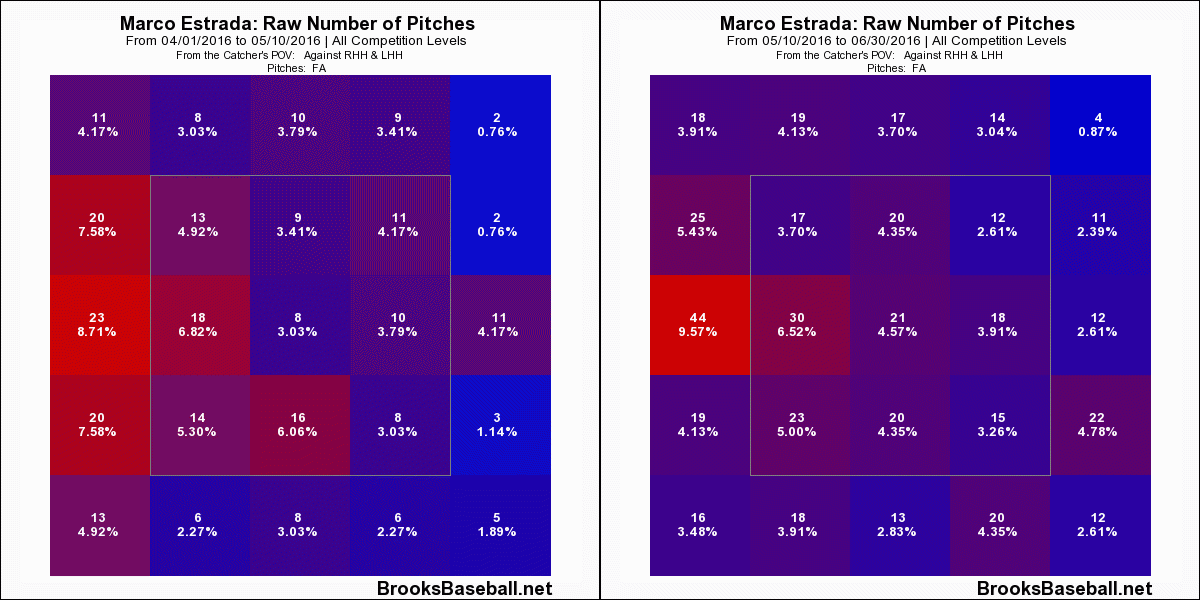

In the last update, I noted how Estrada had gone from working in the upper regions of the zone in 2015, to working on the edges of the strike zone with the fastball, especially to his arm side. In the last couple of months, however, Estrada has started throwing a lot more over the plate.

Given the increased fastball usage over the heart of the plate, one would expect Estrada’s walk rate to shrink. It has actually increased somewhat, from 9.2 percent in the early parts of 2016 to 10.8 percent since. The biggest reason is that batters simply aren’t swinging as often, despite the “meatier” fastballs. Hitters are offering at just 38.3 percent of Estrada’s heaters since May 9, down from 43.2 percent before May 9.

He is also throwing the slowest fastball of his career, at 89.2 mph (again, not including the July 2 start). As a result, when batters do swing, they’re actually making more contact than ever before (85.8 percent compared to 84.5 last year and 80.7 percent for his career).

So, Estrada’s throwing a slower fastball over dangerous parts of the plate, with more contact and fewer chases. And batters are hitting just .182/.287/.350 on the pitch with a 20.1 percent strikeout rate. How is that possible?

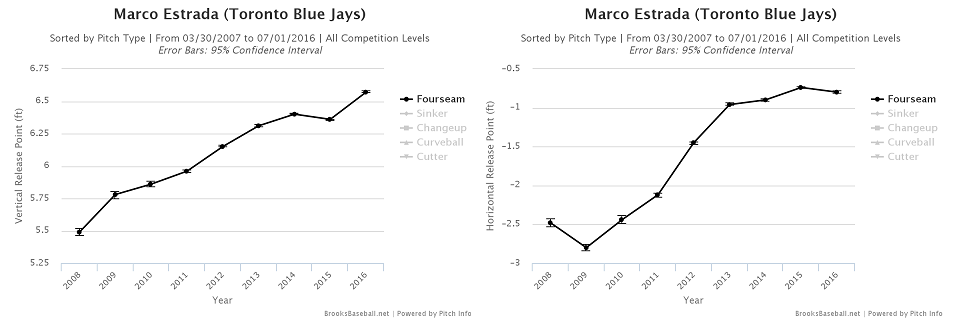

There are two reasons. The first is related to Estrada’s release point:

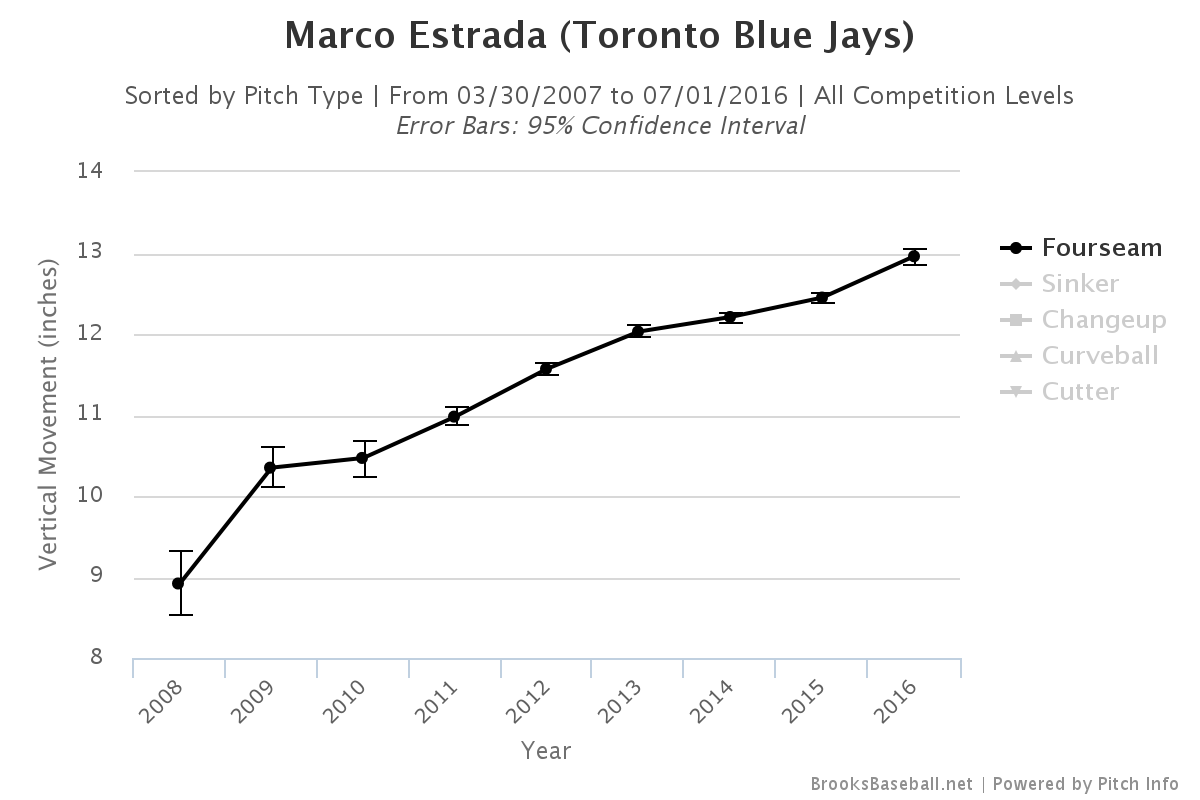

Estrada is also releasing the ball higher than he ever has, with almost the most straight vertical horizontal release of his career, which gives him better downhill plane on his fastball. It has also led to his fourseam fastball spinning more straight up and down than ever before, at 187.7 degrees (180 is pure backspin). Last year he was at 193.5 degrees (league average for righties is 214.3). As a result, Estrada’s elite spin rate, “rising” fastball is falling at an even slower rate than before.

Estrada is now getting 13 inches of “rise” on his fastball, almost a full inch over the next highest, Clayton Kershaw, and over five inches more than a league average fastball. It’s just really hard for hitters to adjust to a ball that doesn’t fall at a rate that they’re used to and as a result you see a lot of very weak popups. Estrada leads the majors with a 17.6 percent infield fly rate, a full 2.1 percentage points over the second place holder, Hector Santiago.

The other thing that makes Estrada so tough to hit, of course, is the bugs bunny changeup.

However, it’s not just the changeup itself – which is of course unbelievably good – it’s that the changeup and fastball mirror each other so well.

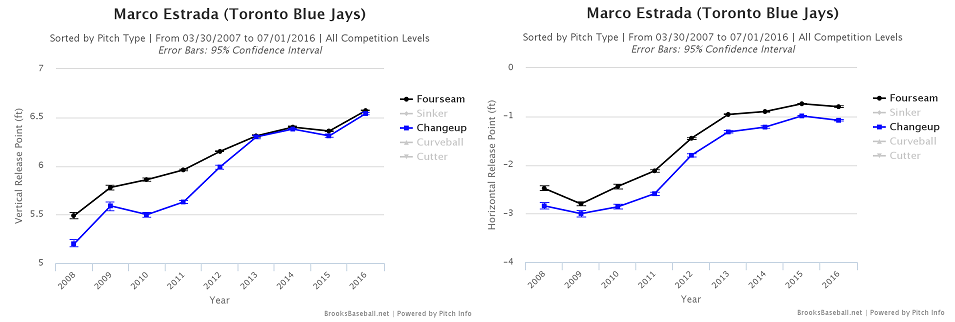

We talked about the release point change on Estrada’s fastball. Let’s compare it to the changeup:

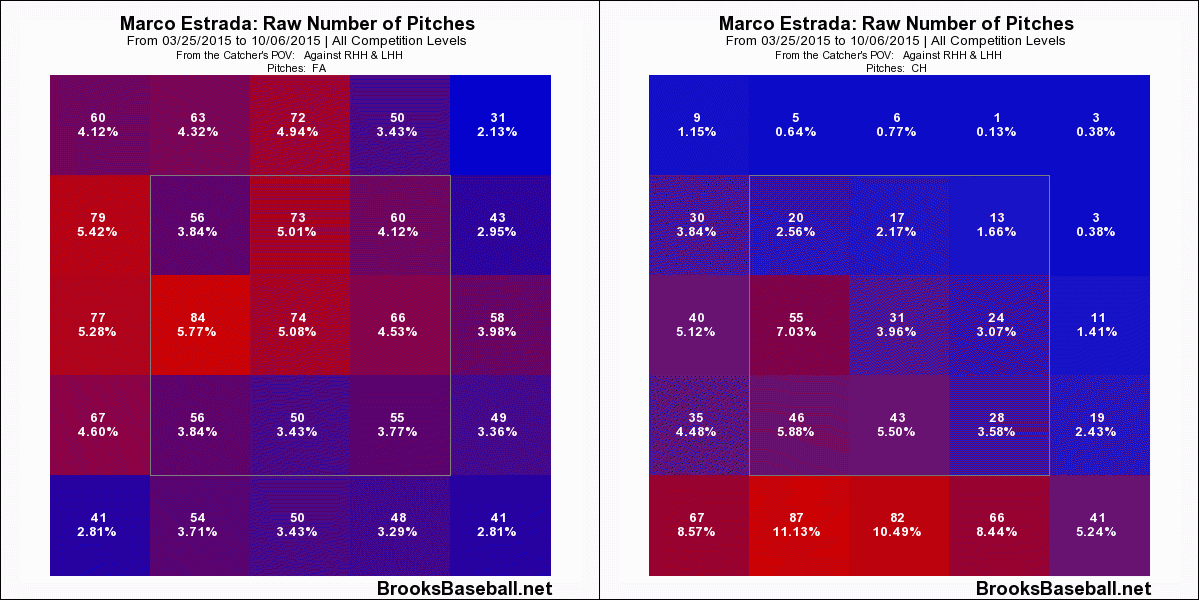

The vertical release point is almost completely identical now, and the horizontal release is within a couple of inches, which makes it almost impossible for a hitter to pick up the difference out of his hand. However, that’s just part of what makes a changeup deceptive. If you’re consistently throwing them in different spots from the fastball, it’s pretty easy for hitters to recognize the difference. This is why last year, Estrada’s changeup location looked like this:

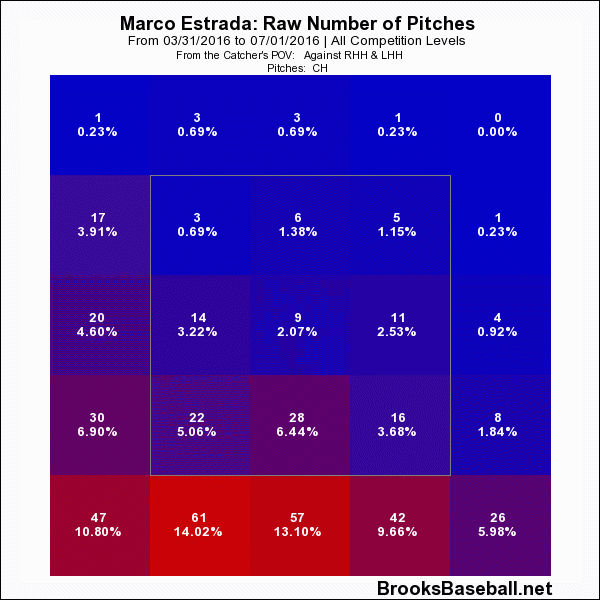

As you can see, both the changeup and fastball were being used slightly higher in the zone. This year, we’ve already shown that Estrada is working more down in the zone with his fastball, and when we look at the change, we can see just why he’s so tough.

With that movement on the fastball, and then that much deception on the changeup, it’s just so hard for a hitter to react properly, even if pitches are only topping out at 90 mph. Also, the changeups down and out of the zone are now generating way more swings and misses with the matching fastball; hitters are missing on a whopping 42 percent of swings against Estrada’s change. This is a career high (previous best was 37.9), and well clear of the league average of 31 percent. As a result, his overall strikeout rate has risen to 24.1 percent, well clear of last year’s 18 percent.

When you add in Estrada’s unpredictability with that deception (he’ll double up on a changeup nearly 30 percent of the time, compared to the league average of just over 20), you get a pitcher who went 12 straight starts of six innings or more while allowing five or fewer hits. That’s also how you lead the league in batting average against two years in a row.

Advanced metrics still don’t look too kindly on Estrada, but they ignore all the things he does to defy the BABIP-gods. Soft contact and pop ups tend to turn into outs, and that’s how Estrada gets things done.

Estrada has turned into this team’s ace, and it doesn’t seem to matter who is calling the pitches. Last year he was working up in the zone to get popups and strikeouts with the fastball. This year he is working down in the zone to get strikeouts with the changeup. It doesn’t seem to matter, he just gets it done. Hopefully he heals up and can continue his dominance in the second half of 2016 en route to a postseason berth.

Lead Photo: Nick Turchiaro-USA TODAY Sports

Excellent article with very well supported and explained analysis!

Thanks!