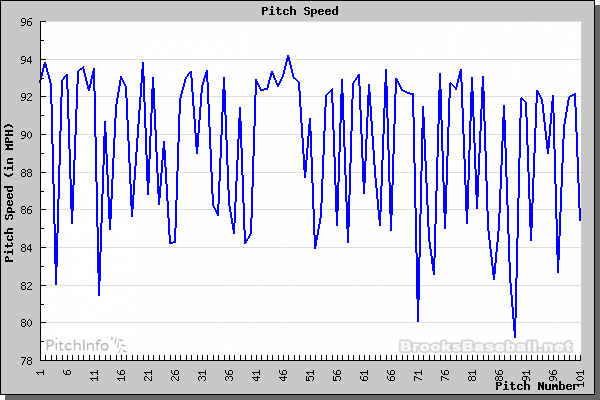

I must confess, I didn’t start this piece out with the idea of making declarations about Aaron Sanchez and his arsenal on the mound. I started, quite innocently, with a pitch chart from Brooks Baseball. For those of you who might not be familiar with the chart I am talking about, let me illustrate first, and then explain.

This is a Marcus Stroman pitch chart. Why did I pick a Marcus Stroman chart when this piece is about Aaron Sanchez? Because Stroman’s chart looks how a starter’s velocity chart should look. As you can see, it marks each pitch by its velocity on the vertical axis and its pitch number on the horizontal. It’s one way to look at a pitcher’s performance in one glance. You can see, reading from left to right, if a pitcher is tiring by looking at the max MPH on the fastballs. Stroman loses about one MPH over his first 90 pitches, and then suddenly another one in his last ten pitches. It’s nothing that should set off alarm bells, but he was tiring. You can also see that he only used about five of his slow curveballs all night, way down there at 79-82 mph, but mixed his pitches and velocities around for the whole outing. Stroman’s chart looks normal. He mixes his pitches well, and he’s know for having five or six good ones at his disposal. This is how, we are told, he keeps hitters in check.

Now that we’ve established what a pitch chart from a successful starter with a wide mix of pitches looks like, we will shift our focus to Aaron Sanchez. Sanchez battled, and brought under control to some extent, wildness as a starter in 2015, and then proceeded get injured. After the injury he returned to the bullpen. With no worries about facing a lineup for the second time, or so the conventional wisdom goes, he could focus on his best pitch, a 96-98mph sinker. Even as sinkers go, it’s a remarkable pitch.

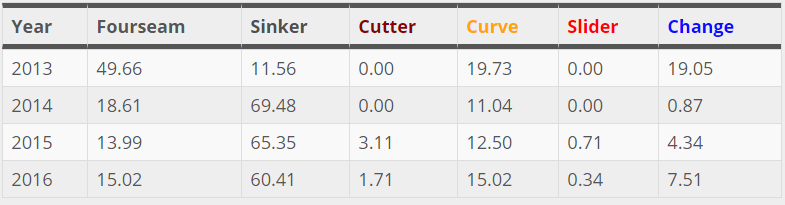

In 2016, of course, he earned a slot in the rotation again. According to popular theory, he needs to find a three pitch mix in order to survive multiple times through a big league lineup. His pitch mix from each year in the majors is as follows.

Now that’s not a big change from 2014 to 2015 when viewed as an entire season’s worth of data. A couple fewer sinkers, more curves and more changeups. Also, it looks like a three or four pitch mix: Four Seam, Sinker, Curve, Change. According to the velocity charts, the sinker and four seam fastball come in at the same average velocity. They are two different pitches, but they are equal in how long a hitter has to react.

I would take a position that says the pitch mix shown above is incredibly misleading. We need to zoom in. If you read my features regularly, I’m a big fan of zooming in to see what’s going on. Here is the game by game breakdown for 2016.

In Tampa, Sanchez (or possibly Martin if you feel he is the guiding force) really tried to mix it up. He threw almost 30 percent offspeed stuff, and it worked; he got a lot of swings and misses from a very aggressive Rays club. One run, seven innings, 91 pitches. And because it worked so well, Sanchez dumped the changeup almost entirely when facing the Yankees. That makes no sense, but it’s true! He threw more sinkers and featured more curveballs. The result: One run, six innings, 97 pitches. And, of course, because the curveball worked so well, he threw fewer of those against Boston, forgot about the changeup entirely, and it worked too! This time: One run, seven innings, 105 pitches. Everything works!

Who is really in charge of the choices here is a difficult to tell, since I can’t zoom inside a player’s head to learn the reasoning behind these choices. The changing pitch mix might be a result of scouting reports, or his command of certain pitches on a certain day. I don’t know. The fact remains, Sanchez does not need to “keep hitters off balance” to be successful. So far they haven’t solved any of his patterns. And as we are about to see, “patterns” may be overstating his pitching strategy here.

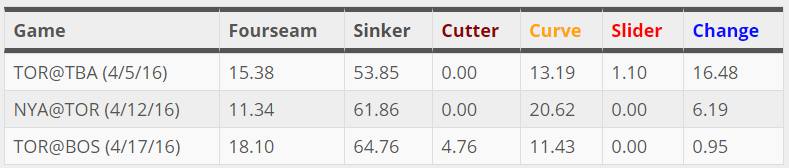

Now we finally get to the image that sent me on the long quest for answers about Aaron Sanchez’ pitch mix:

This is the Sanchez velocity chart for his start at Fenway. I have added some green lines for effect. Between pitch 21 and pitch 83, Sanchez threw exactly two pitches that were not fastballs. That’s 60 out of 62 pitches where Boston players had a pretty good idea what would be coming next. If you’re curious, the pitch f/x record shows one of those curveballs was a called ball, the other a called strike.

That’s kind of crazy. Historically Sanchez has been a contact guy with big groundball tendencies. That’s still true. Yes, he had a bunch swings and misses against the Rays, and we watched them swing early and often for the whole four game series, but Sanchez is still a contact guy. Some things have looked better though. When he was starting in 2015, he was throwing 58 percent strikes. So far 2016 has seen 63 percent strikes thrown. His first pitch strike percentage is up from 53.2 percent to 59 percent this year. As a result, batters should know what’s coming now, and expect it to be in the zone. Yet for some reason, they still can’t hit it hard. That’s good. It means that 96 mph with wicked movement is the real tool in Sanchez’ arsenal.

Of course, I wondered, is this use of exclusively hard pitches a weird exception? Should Sanchez be trying to mix in that third and fourth pitch to keep hitters “honest” as they say? Well, in 2015, he had the opportunity to try a lot of things.

Let’s look closer at what kind of arsenal got him what sort of results. Until the April 27th start in Boston, Sanchez had all kinds of trouble finding the strike zone, meaning that those mixes might reflect far more of a struggle with command than a real plan of attack. So instead we’ll start when he began to throw more strikes. On May 2nd, he threw 66 percent fastballs, and the most curveballs of his career. On May 8th he went back up to 75 percent fastballs, and threw seven innings with five walks, but zero runs allowed. He walked six in against Cleveland in 5.2 innings. On May 13th, the threw more four-seamers than in any other start. He walked four while giving up five runs to Baltimore, in 5.2 innings pitched. From this point on it looks like there was a decision to throw the fastball more, and when it worked, (three walks and three runs in 7. 1 innings against Anaheim), they decided to throw it even more. And then more. And then even more. For a starter, throwing 90 percent fastballs is supposed to be ridiculous. Sanchez did it anyway. Look what happened:

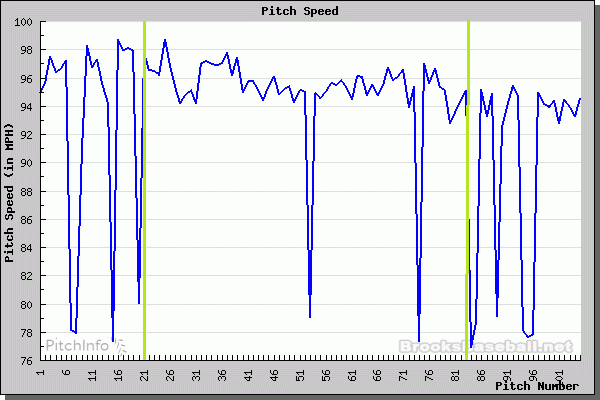

Eight solid innings against Houston. No walks. Two runs, only one of which was earned, both in the ninth inning. I present to you the velocity chart from that game:

I’ve added green bars again. Again, lets look at how many fastballs he used in-between the bars. Between pitch four and pitch 64, I count two changeups and two curveballs. Houston didn’t even have to worry about the four seam fastball. It was wall-to-wall sinkers for four innings. There’s your evidence that the plan of attack against Boston wasn’t necessarily a fluke. Just like the Red Sox last week, the Astros couldn’t figure out how to hit the same pitch, coming at them over and over again.

When Aaron Sanchez keeps the baseball in the zone, and gets the first pitch in the zone, he’s very, very difficult to square up. This has been true even when batters should know what he’s doing. Not every pitcher can say that. If controlling the fastball is the key, let him focus on it as much as he wants. The curveball and the changeup can be implicit weapons, not explicit ones. There’s nothing in his career as a starter that says he’s any better using three pitches.

So, what other starting pitchers are reliant on the fastball? There were three pitchers in 2015 who qualified as starters and threw over 70 percent fastballs: Lance Lynn (85.4 percent fastballs) is close in K/9 and BB/9, but is a fly ball pitcher (44 percent GB rate). Bartolo Colon (83.8 percent fastballs) throws 88 mph, not 95, so it’s not the same method as Sanchez. Mike Pelfrey (73.9 percent fastballs) can’t strike anybody out (5.12 K/9 career), and uses a split finger as his second pitch. He has also struggled to do more than eat innings for the last few years. This means that if Sanchez focuses on the fastball, he’ll be doing it in a way unlike any pitcher currently starting in MLB.

Aaron Sanchez is a truly unique animal, and Jays fans should be happy to have him.

Lead Photo: Bobb DeChiara-USA TODAY Sports