The 2016 season opens for the Blue Jays in Tampa Bay against the Rays, and it’s an interesting coincidence, at least in the purview of this article, given the way that the new Toronto front office appears to be constructing its pitching staff. It’s certainly not a bad strategy to mimic; despite getting just 24 total starts from Alex Cobb, Drew Smyly, and Matt Moore, the Rays pitching staff allowed the fourth fewest runs in the American League in 2015. It wasn’t all defense either, as their team ERA and FIP of 3.74 and 3.91 were also fourth best in the American League. With the rotation vulnerable and the depth exposed, the Rays did exactly what any smart, analytical organization would do: they overextended their bullpen. Wait, what? The underlying thought is that the Rays were cognizant of the times through the order penalty, and were ensuring that the opposition didn’t take advantage of their fatiguing depth starters who had been thrust into the spotlight.

What is the times through the order penalty (TTOP)?

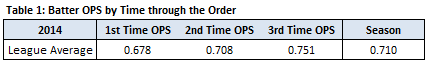

While not actually a penalty, per se, the TTOP shows that as a pitcher faces a batter more times in a game, their performance gets worse – or from an alternative perspective, the batter’s performance improves. In late 2014, Brett Talley of Fangraphs identified a list of candidates for potential regression based upon an unsustainable level of success as they faced batters for a third time. In the article, he laid down a nifty little table which I’m going to borrow for this piece.

In short, what the above table shows is that in the first time through the order, the pitcher has a notable advantage over the batters. However, the second time through is worse, but only to the point of being a neutral matchup. Meanwhile, the third time through is nothing short of a nightmare for a starting pitcher. In the third time through the lineup, batters have an OPS that is six percent higher than their season mark, and 11 percent better than their first time through. The reasoning behind this relationship has been studied extensively, but from what I can gather, a single cause cannot be drawn out from the mess of variables. Instead, it’s likely that some combination of the pitcher tiring and the batter making adjustments from previous plate appearances contribute to the discrepancy. Still, while the origin of the effect may still be shrouded in mystery, the impact of the effect is beyond question.

Much of the legwork for the TTOP was done by Mitchel Lichtman when, in November 2013, he wrote a pair of articles looking at the TTOP phenomenon under the microscope. At the end of the first article, Lichtman came to a number of interesting conclusions. Though he used wOBA instead of OPS to evaluate, his observations meshed with the above table, where the pitcher is better than usual the first time through, and then gets progressively worse the longer he remains in the game. He also observed that a pitcher’s career times through the order patterns are have almost no predictive value. Finally, while the wOBA values may be slightly different, both good and bad pitchers suffer from the TTOP at around the same magnitude.

Following the initial article, Lichtman received a lot of feedback from commenters asking how the TTOP effect may vary depending upon the type of starting pitcher; with specific questions around fastball usage and arsenal diversity. Once again, his observations were very interesting.

Starting pitchers who rely almost entirely on fastballs (>75 percent) had the most immediate and devastating TTOP impact, while starting pitchers who threw less than 50 perfect fastballs had the slowest and shallowest decline as a result of the TTOP. His analysis showed that batters facing fastball heavy starters improved their wOBA by 47 points the third time through, whereas batters facing the fastball light starters improved their wOBA by just 18 points over the same period. This conclusion passes the logic test, as one would reasonably expect batters to improve at a more rapid pace when their focus can be narrowed to a single pitch.

After focusing specifically on fastball usage, Lichtman turned to arsenal diversity, splitting pitchers into groups based upon the number of different pitches thrown more than 10 percent of the time. As expected, the overall trend was similar to that observed with fastball usage, where the starting pitchers who threw just one pitch more than 10 percent of the time had the largest decline the third time through, at 36 points of wOBA. Starters who feature two, three, and four pitches saw batters improve by 34, 28, and 24 points of wOBA, respectively, over the same interval. Perhaps the most interesting point from this arsenal diversity analysis was the timing of the aforementioned declines. The two, three, and four pitch starters were steadily worse each time through, whereas the one pitch starter was considerably worse the second time through, but saw only a minor decline in performance after that.

How does the times through the order penalty apply to the 2016 rotation?

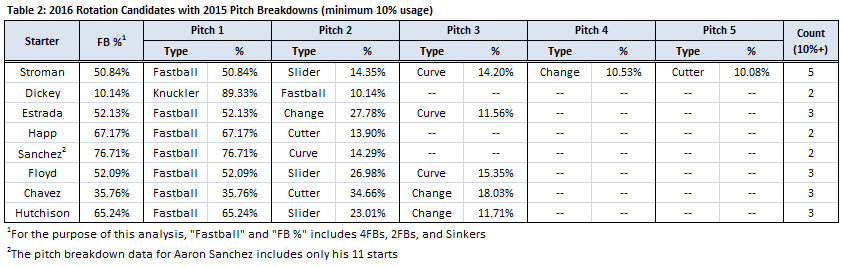

Looking first at the fastball usage trend, only Aaron Sanchez (76.71 percent) eclipses the 75 percent upper threshold identified by Lichtman. Note that this usage rate is exclusively from his 11 starts in 2015; his sinker/ four seam fastball usage rate as a reliever was 84.84 percent. This suggests that Sanchez could be the most susceptible to the TTOP – more so than any other rotation candidate – and should be watched the closest as he turns a lineup over for a second or third time. For a pitcher so heavily reliant on the fastball, if the opposition starts to pick it up or he loses command and has nowhere else to turn, he could get cratered in a hurry.

J.A. Happ (67.17 percent) and Drew Hutchison (65.24 percent) are the most susceptible among the middle tier (between 50 and 75 percent fastballs). Happ is likely more so affected than Hutchison because his next most frequently thrown pitch is another fastball-esque offering (cutter). Conversely, Marco Estrada (52.13 percent), Gavin Floyd (52.09 percent), and Marcus Stroman (50.84 percent) are arguably the least susceptible to the TTOP of the middle tier thanks to their near-50 percent fastball reliance. Jesse Chavez is on the low end of the spectrum, as his sinker and four seam fastball usage totaled just 35.76 percent; firmly establishing the right hander in the safest group according to Lichtman’s conclusions. Batters facing Chavez-type pitchers were worse than their season average in both their first and second time through. While Sanchez-types lose 47 points in wOBA against their third time through, Chavez-types lose just 18 points – a considerable improvement. This isn’t to say that Chavez has an endless leash, but if he’s cruising through the lineup’s second trip, Gibby probably doesn’t need to have his finger hovering over the panic button in preparation for the third.

Marcus Stroman stands as a man among boys under the arsenal diversity header. Even when his sinker and four seam fastball are summed into one offering, he still features five different pitches more than 10 percent of the time. Lichtman’s analysis didn’t expand the study to starters with five pitches, but those who throw four pitchers suffered the TTOP at the slowest rate; losing 20 points of wOBA against their third time through, whereas those who threw three, two, and one pitch(es) at least 10 percent of the time lost 22, 28, and 31 points. We saw, both in September and into the postseason, that because of his deep arsenal, Stroman can plan for lineups in entirely different ways. On September 12th against the Yankees, he went 51 percent fastballs, 22 percent curveballs, and 14 percent cutters. When Stroman faced the same lineup 11 days later, his fastball usage dropped to 37 percent, his curveball usage dropped to 3 percent, and he instead attacked with sliders (27 percent) and changeups (23 percent). Unpredictability is an asset, but the fact that Marcus Stroman can be unpredictable with five different plus pitches is what makes him a legitimate ace in the making. That’s also exactly why you should expect to see him pitch into the seventh and eighth innings regularly in 2016. At 5-foot-9, Stro is poised to be one of baseball’s strongest workhorses.

Once again Aaron Sanchez and J.A. Happ find themselves potentially wielding the short straws, but interestingly, despite their similarities, the general narrative is that they need to move in divergent directions to be successful. Sanchez is all fastballs (76.71 percent) and curveballs (14.29 percent), and most agree that he needs to continue to advance his breaking ball while also developing a reliable third pitch to shake the reliever tag. On the other hand, Happ experienced much of his recent success by basically abandoning his breaking and off-speed pitches and going hard-hard-hard with everything, which the internet has lauded and encouraged. The two theories appear to agree that among the traditional starting pitcher candidates on the Blue Jays roster, if Gibby’s going to go with the quick hook before a starter faces his 19th batter, it will likely be to grab Sanchez or Happ.

Will the Jays consider the times through the order penalty?

Traditional was used purposefully in the previous paragraph, as the embers of this article were first sparked back in October when John Gibbons went to retrieve R.A. Dickey in the fifth inning of a game the Blue Jays were ahead 7-1. Media and fans alike were stunned, wondering (rather loudly, and to anyone who would listen) how you could pull a guy one out away from qualifying for his first postseason win, in a six run game no less. The bottom line is that Dickey faced nineteen batters, and 17-18-19 went fly out to centerfield, single to centerfield, line out to centerfield on a full count. The Rangers were on the knuckleball, and Gibbers had no interest in letting Shin-Soo Choo – who was already 2-for-2 when he strode to the plate – see it a third time.

Game four of the ALDS obviously means more than say, game 45 in May, so whether or not Gibbons continues to manage so aggressively with any starter is still yet to be determined. But if the organization’s offseason has been any indication, the front office is at least leaving the door open for the possibility. In order for such a philosophy to ascend from concept to reality, the roster needs to have a stable of pitchers capable of throwing multiple innings in relief. While none resulted in signings, the Blue Jays were reportedly in active pursuit of Craig Stammen, Yusmero Petit, and Joe Blanton in hopes of augmenting their bullpen, all of whom perfectly fit that criteria.

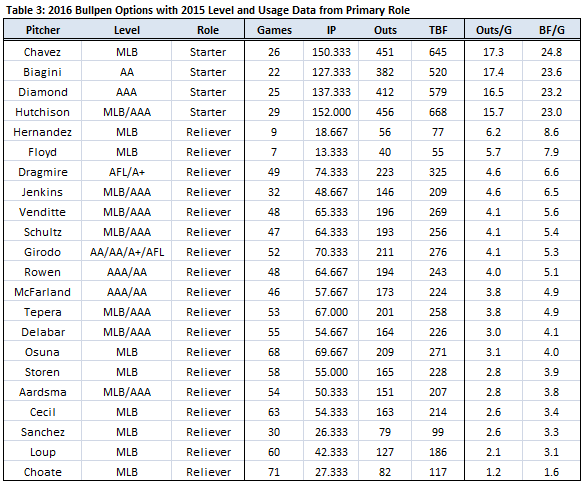

The seven spots in the Opening Day bullpen are still largely in flux behind the big three of Drew Storen, Brett Cecil, and Roberto Osuna. Storen and Cecil. As Table 3 below shows, in 2015, Storen and Cecil averaged 3.9 and 3.4 batters faced per appearance respectively. While I expect Osuna to be right there with Cecil holding on to small leads in the late innings, I suspect his utilization pattern will be quite different from the other two. He threw 70 innings across 68 relief appearances in 2015, and while that equates to just 4.0 batters faced per game, most, Gibby included, seem to think that number is going to rise. In USA Today John Gibbons was quoted as saying, “Osuna can give you more than one inning. Drew’s probably limited to one inning. That’s kind of who they are.” On nights where on of Storen or Cecil is unavailable, it would be unsurprising to see Osuna pitch two innings.

Beyond those three, the bullpen competition really opens up. Despite becoming the poster boy for meltdown innings last year, Aaron Loup almost assuredly has a leg up if his arm injury proves minor, and with his regression into a pseudo-LOOGY, he’s another one-and-done type of pitcher (3.1 batters faced per game).

At least one of Jesse Chavez, Gavin Floyd, Drew Hutchison, and Aaron Sanchez will find purchase as the fifth starter in the rotation, with the other three finding themselves in a battle for the bullpen. The loser(s) of the spring skirmishes, likely those with options (Sanchez and Hutchison), also face the possibility of a demotion to the rotation in Buffalo as insurance. Still, this is where the roots of any philosophical shift have the potential to really take hold. All four have been starting pitchers within the last two seasons (even Floyd!), and if tasked to work in relief, could easily come into a game in the fourth, fifth, or sixth inning and turn the opposing lineup over one or one-and-a-half times before handing the lead off to one of the late-inning dynamos.

Most of the other remaining candidates for the final couple of spots in the bullpen also fit the mould as potential multi-inning relievers extremely well. Pat Venditte, Roberto Hernandez, Ryan Tepera, Bo Schultz, and even Chad Jenkins have found varying degrees of success in baseball’s uppermost levels, facing five-plus batters per relief appearance. Even last December’s Rule 5 pick-up, Joe Biagini, feels like a legitimate option. The 24 year old has been a starter his entire minor league career, but in short bursts this spring, his fastball has been registering 95’s and 96’s on the gun, giving off the vibe that he might be the type of arm that could play up in relief when tasked with throwing twenty or thirty pitches and facing a lineup just once. Over the winter Andrew Stoeten offered forth the hypothesis that the team may even see him as “Liam Hendriks 2.0”, and while, no one can be Liam Hendriks, it’s an interesting thought worth consideration. The periphery of the 40-man roster and the non-roster invitees also boast relief options with some length in former starter Scott Diamond and relievers Brady Dragmire, Chad Girodo, Ben Rowen, and Blake McFarland, the latter four of whom averaged 6.6, 5.3, 5.1, and 4.9 batters faced per 2015 appearance.

For the sake of argument, let’s envision an entirely plausible scenario in which Gavin Floyd wins the fifth spot, both Aaron Sanchez and Drew Hutchison are sent to Buffalo to stay stretched out, and Aaron Loup opens the season on the 15-day disabled list. In this case the Blue Jays head north with a bullpen comprised of Storen, Cecil, Osuna, Chavez, Venditte, Tepera, and Biagini. John Gibbons would have a dynamic mix of arms capable of handling any situation, and the length offered by the two converted starters in Chavez and Biagini would allow him to be hyper-aggressive with his bullpen and force a completely different look on opposing batters as soon as they appear to be getting comfortable with one of his starting pitchers. It would be an unprecedented approach outside of the confines of Tropicana Field, and could give the Blue Jays a much-needed edge as they battle four other strong teams in hopes of claiming their second AL East title in as many years. Mark Shapiro is known around baseball for his progressive thinking, and this might be the perfect opportunity to use that analytical mindset to directly improve the product on the field.

Lead Photo: Kim Klement-USA TODAY Sports

This article rules.