I want to begin by stating that, first and foremost, I don’t believe baseball has a problem. Baseball has, instead, a developing situation.

Although the Postseason was filled with a billion home runs, and that’s definitely unusual, it’s not just homers that make up the new state of the game. Baseball feels ‘odd’ right now. And although that strange vibe might be under the microscope in the playoffs, it certainly didn’t start there. Let’s look at some things that we see more and some things we see less. Then maybe we can figure out why these changes have affected the feel of a ballgame, while not really making it any less ‘fun’.

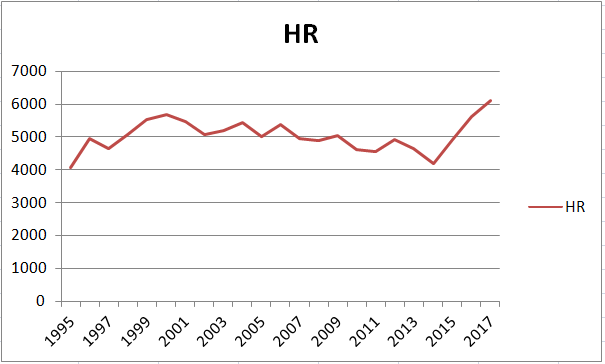

The first thing anybody talks about is the spike in Home Runs. It’s tough not to talk about. So let’s make a chart and talk about it.

GM Chrysler! What is that line doing at the end there? That’s every season home run total, right from the post-strike season, right through the heart of the Steroid Era. Nothing compares to the rise from 2015-2017 at all. And when the writers ask about that, they get one of these from the league.

Okay, sure, I’ll move along, but only because I have other charts.

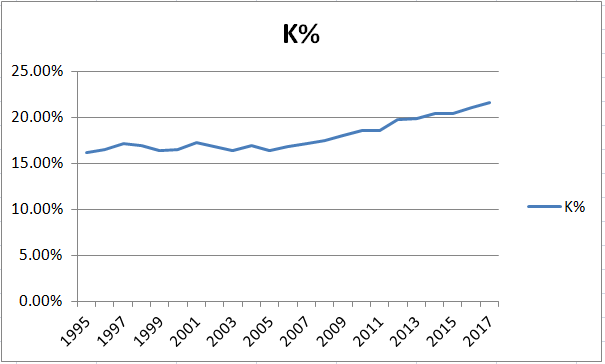

Specifically, we have league strikeout rate – with a different trend, but also one that fundamentally affects the way the game is played.

So, it’s not the fireworks of the previous chart. The league strikeout rate hit 17.5 percent, back in 2008, which was an all-time high. And then it hit a new all-time high in 2009. And then it hit a high again. And again. And again, and again, and again. Then it held steady. Then it set a new record again, and again. If this had happened to the home run rate, it’s possible the ball would be two ounces lighter and have a thick nougat center by now, just to rein in the madness. But the league’s answer to the seemingly unstoppable creep of strikeouts has been to…talk to the umpires about maybe calling the zone better. Or maybe changing the zone. But nothing extreme. Nothing that would, say, result in an additional five percent of the plate appearances ending with a batter turning 180 degrees and strolling back to the dugout. If that happened it would be madness. Well, except for when it already did happen over the last 8 years.

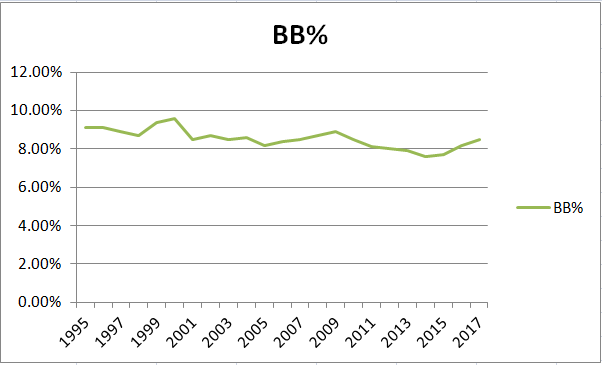

So, about the umpires calling the zone better. Did they do that?

Weird, maybe they are calling more balls. At least since 2014. Seems like it’s counter-intuitive, but that jump in home run rate coincides with a trend reversal in the walk rate. Shouldn’t guys selling out for power also have less patience? What about the lowly single? Surely the great advances in defense over the last few years…the almost constant shifting…surely they have killed the single.

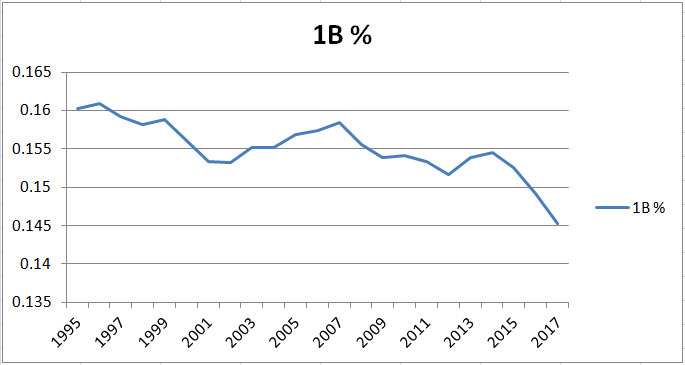

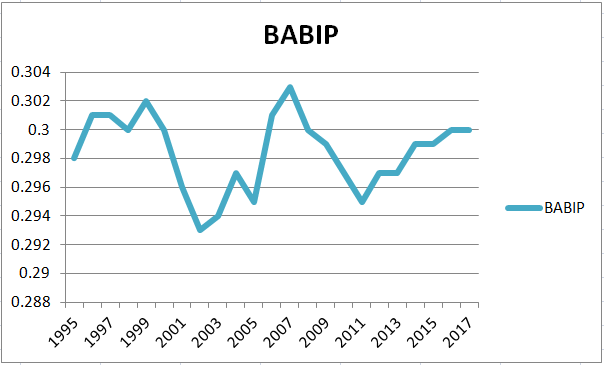

All those singles, dead. Did anyone think of their families? Okay, so, ultimately, I could do this with double and triples and hit by pitch and so on, but I will try and keep my observation a little more focused. We have seen defenses deployed in order to limit the number of singles, but have seen the number of doubles increase slightly over the same period of time. In fact, when you look at BABIP, which is a measure of how many balls in play are turned into outs, you get the most remarkable graph of all.

This looks like a very large swing, until you look at the scale on the side. The lowest value is .293, the highest is .301. In the last 25 years, with everything else that’s changed in the game the following remains true: if you put the ball in fair territory every plate appearance, it would be a hit just slightly less than 30 percent of the time. That seven point swing in BABIP occured over the same span where actual batting averages had a 20 point swing. Yes, you can play your defenders wherever you like, but the hits will still be out there.

What does it all add up to, then? More home runs, walks and strikeouts with fewer singles has resulted in a net increase in runs. From 19,761 in 2014 (was that The Year of the Pitcher?) up to 22,582 in 2017. That increase, though, has been a result of fewer overall balls in play. Here’s why I think that makes a fundamental difference to the feel of the game.

Baseball, for the committed fan, is about tension, probability and uncertainty. A runner on second base with nobody out means the pitcher is probably in trouble, but he might get out of it. Each subsequent pitch is very tense. A hard line drive three feet over the pitcher’s head is probably a base hit, but the shortstop might be running to cover second and close enough to snag it. A runner trying to stretch a double into RF into a triple is gambling against the skills of as many as three of the fielders, as well as his own legs. Really, as soon as the ball leaves the pitcher’s hand, nobody in the ballpark knows for sure what’s going to happen in the next four or five seconds, and it’s gripping.

There isn’t really an analog to these things in soccer, basketball or hockey, because even as the offense and defense put pressure on one another, there isn’t time to discuss the free flowing nature of the action. There is also a different kind of emphasis because the offensive team has direct control of the ball (or puck) and they are making decisions about what to do with it. In these other sports, we can talk about whether a player made a fundamentally good decision and draw a line to whether that led to a great result. In baseball, there is a gulf between a good decision and a good result, an equation with randomness built in, that hitters and pitchers have been trying solve for over 100 years.

Home runs, strikeouts and walks are some of the least randomized results in baseball. Something about seeing so many of the Three True Outcomes reminds me of this:

Yes, I know, I’m old. Is this better?

What do old computer baseball games have to do with real baseball in 2017? They lacked variety. If your timing is correct, and you move the little stick and buttons consistently, you can virtually guarantee certain outcomes. I could bunt with the first two players in Hardball and end up with runners on first and second with nobody out almost 80% of the time. I’m sure you had friends who could ‘always’ strike out the computer with a secret (or not so secret) combination of pitch types and locations. Home runs tended to go to only a few different sections of the bleachers and nothing ever hit the foul poles or had the manager run out to argue fair or foul. If a ball was hit down the line, you could tell by the arc whether or not the third baseman was going to make that catch without even waiting a fraction of a second. These games had, by technological necessity, a very limited number of possible results. Real baseball is supposed to be a game of infinite possibilities. Take away the fences and the playing field could literally go on forever. Only that’s not the direction we seem to be going.

Don’t think that this is a complaint. It isn’t. This is just an observation about how the game is changing. It is always changing. It changed when they allowed pitchers to throw overhand, when they livened up the ball, when they expanded the leagues, and when everybody looked the other way on steroid use. Each of those changes was notable, and will always be considered important in the context of the history of the game. What’s happening during this new era (The Statcast Era? The Juiced Ball Era?) is that some old adages are dying. The reasoning seems to be that there is one optimal way to do everything. That sounds kind of obvious, but it isn’t how baseball has operated up until very recently.

It used to be that some hitters were told to pound the ball into the ground and outrun it, some were told to try and slap the ball the other way, and even others were told to pull it to generate power in the air. Nobody does those first two things anymore. Those ideas have faded because it turns out if you do the third thing – and you are only mediocre at it – you can still have enough success that your overall results will probably be better than those first two strategies. It used to be that certain pitchers were told to emphasize control and try to induce weak contact by pitching to specific locations, while others were forgiven a certain lack of control if they could throw the ball harder and rack up lots of strikeouts. Now most hurlers are trained to throw as hard as they possibly can. As it turns out, even the best hitters have trouble with baseballs thrown at 98 mph, because the human brain and body have a physical limit as to how fast and accurately they can react.

And the result is the trends we see over the last three or four years. Whether or not there is less excitement in the game is entirely up for debate. There certainly seems to be less variety, though. Baseball as a game with more certainty, less of the unknown quantity. Now that feels odd.

Good article, interesting observation – the concept of table-setting/balanced lineups seems to have been replaced with having 9 guys who swing for the fences. There’s always an adjustment tho – I’m just not sure what that will be. Maybe in this environment Dee Gordon types will be available on the cheap … and some team can become competitive with a low-cost, low-power/high OBA lineup.

Interesting thought, there is always an adjustment. I would also like to make it clear that I didn’t make the first comment on my own article.

That’s kind of what the low-cost, low-power Royals did in 2014-15. Make lots of contact, be aggressive on the basepaths, and force the defense to make perfect plays in order to stop you.