This post is going to be about how Dioner Navarro is a bad pitch framer. However, before we get into it, lets get one thing out of the way: one of the best things about baseball is that a player’s value is segmented into tools. Billy Hamilton is a bad hitter, but his defence and speed allow him to play baseball for money regardless.

Dioner Navarro is a bad pitch framer, but he does a lot of other things well that make him a good catcher overall, in my opinion. He calls a great game, he blocks balls, he limits the running game, he has decent plate discipline, he’s a good clubhouse guy, and he’s Marco Estrada’s closest confidante. This isn’t an assessment of whether Navarro is a good catcher, it’s a statistical update on his pitch framing ability.

The Quickest Possible Primer

Under all the fancy regression models, framing statistics are basically just looking at called strikes. How many extra called strikes your catcher is getting you and how many he is losing you. This is broken down into two intuitive categories by Matthew Carruth at StatCorner:

oStr%: The percentage of pitches caught outside the strike zone that are called strikes. The higher this is the more strikes you are “stealing”. The average in 2012 was 14.5%.

zBall%: The percentage of pitches caught within the strike zone that are called balls. The higher this is the more strikes you are “giving away”. The average in 2012 was 7.2%.

That’s the nuts and bolts of it. The fancy stuff done on top of that at Baseball Prospectus is intended to control for random variables like the batter, the pitcher, and the umpire in order to spit out a more stable and accurate statistic called Called Strikes Above Average (CSAA).

The range from terrible to elite is something like -3% to +4%. That seems super narrow, but extrapolated over a full season at the standard rate of .14 runs per additional strike, that translates into a range of -20 (terrible) to +40 (elite) runs. Every little bit counts when your sample size is 7,000-8,000 balls over a season; you can’t compare it to a hitter who’s getting 600 plate appearances.

Okay, last up is stabilization. In this seminal piece introducing the statistic, written by Jonathan Judge, Harry Pavlidis, and Dan Brooks, the stabilization point of CSAA is pegged at around 30% of a season. In terms of actual balls received, Fangraphs’ Jeff Sullivan pegs it at roughly 1,000 to 2,000.

The Stats

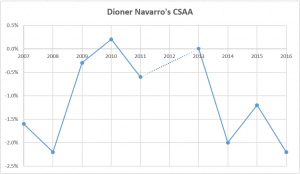

That -2.2% CSAA translates into a -19.03 Framing Runs Above Average which ranks dead last in the majors in 2016. There’s a dotted line skipping over 2012 because he didn’t get enough time behind the plate to give a reliable sample size.

Drilling down into the stats, we can see that his problem is not that he’s been bad at stealing strikes. He’s actually done OK in that department, getting called strikes on 95 pitches that had a 25% chance or lower of being called strikes according to PITCHf/x. That translates into a 6.9 oStr% on a rate basis. If you watch Navarro receive borderline strikes, the first thing you notice is how incredibly still his body is, which makes the umpire less likely to notice that a pitcher has missed his spot.

However, his problem is that he’s been giving pitches away like crazy.

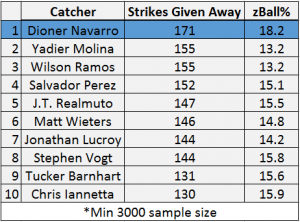

That’s a shocking gap between Navarro and Molina given that Yadi has received 2,721 more pitches than Navarro. And if you think this is a recent trend, you’d be wrong. Navarro’s zBall% has ranked in the bottom 10 among qualified catchers in each of the past four seasons.

The Eye Test

The reason that CSAA is the least volatile framing statistic is because it accounts for so many exogenous factors such as the pitcher on the mound and the umpire. As we’ll see, those factors exert large effects on the granular data. But even with CSAA at our disposal, it feels wrong to condemn Navarro without first looking at some footage.

2016 has been pretty bad, but 2014 was a god awful framing season for Navarro and anyone could see that just by watching. In a Baseball Prospectus piece from May of that year, Ben Lindbergh looked at the early contenders for, “worst framed ball of the season.” Navarro had two candidates in the top-five.

You might give Navarro a gimme on that one given he was clearly expecting something completely different from what Brandon Morrow ended up throwing him. Plus it’s a little ridiculous that umpires refuse to call strikes on dropped balls even if it’s right down the middle.

This next one though.

If we think of the strike zone as a 3D rectangle, Aaron Loup’s fastball moves laterally from the front to the back of the zone. Instead of getting into position to catch it towards the front of the zone, Navarro waits to catch it as it’s exiting the back of the zone and is forced to move his glove in a way that makes this pitch look like a ball to the umpire.

Here’s a similar example of Navarro butchering a sweeping fastball from a lefty, this time from 2016:

You can even see Navarro tapping his chest to let everyone know that was on him. It does look like he set up for a strike further inside, but a skilled framer should be able to snap his glove and catch that pitch on the outer half for a strike.

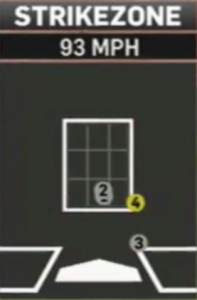

Finally, here’s a called ball that PITCHf/x thought should’ve been called a strike, from a Tyler White at-bat on May 17. Again, it’s a hard throwing lefty on the mound in Carlos Rodon.

Notice how his glove sags a bit and makes it look like that pitch is caught below White’s knees.

Midway through the at-bat, with the count at 3-1, the Houston broadcast pulls up a strike zone graphic and starts subtly trashing home plate umpire Tony Randazzo. “That’s three pitches in the strikezone that he’s called balls now,” says colour commentator Bill Brown.

You can’t assign 100% of the blame to either party, but the fact that Navarro was behind the plate definitely didn’t help Rodon in this at-bat, which ended in a home run if anyone was curious.

Fortunately, the Blue Jays have one of baseball’s best framers in Russell Martin, and judging by how Navarro has started just once behind the plate since arriving in Toronto, Martin should continue to shoulder the bulk of the team’s catching duties with Navarro being used in a DH or backup role. So, Navarro’s framing deficiency shouldn’t turn into a big issue given the limited amount of pitches he’ll be receiving going forward.

However, there are a few valuable takeaways that John Gibbons should keep in mind when deciding how to use Navarro. Combing through the 171 called strikes that Navarro has given away this season, the vast majority seem to be fastballs/cutters/sinkers either low or away. Furthermore, his greatest weakness is receiving hard-throwing lefties.

Looking at the Jays arms, that means it’s probably not a good idea to have Navarro catching Aaron Sanchez and Marcus Stroman, who both love to pound the ball low and away. Ditto for southpaws J.A. Happ, Francisco Liriano, Brett Cecil, and Aaron Loup. That still leaves a lot of room for Navarro to be useful behind the plate, and most importantly gives Gibbons a blessing to keep the Navarro-Estrada battery alive.

Lead Photo: Kim Klement-USA TODAY Sports