It’s no secret that the Blue Jays vaunted offense isn’t quite living up to expectations. Last year’s squad scored 5.5 runs per game, lapping the field by such a wide margin that the second place Yankees were closer to the 26th ranked Reds than the league-leading Blue Jays. This year, the Jays have scored a measly 4.04 runs per game, which has them sitting 20th overall in baseball and 11th in the American League (just ahead of the Yankees).

What makes the Jays’ struggles so baffling is that they have returned with almost the exact same lineup as last year. In fact, the only two changes are the addition of a healthy Michael Saunders and a full-time slate for Justin Smoak. And clearly those two aren’t to blame for the hitting woes, as they’ve arguably been the two best hitters on the entire team.

Instead, it is last year’s right-hand hitting standouts that are disappointing the club. The numbers are down across the board.

The numbers for Josh Donaldson and Jose Bautista are down slightly, but their overall production is still more than adequate, and nobody should really be complaining about those two. However, when we get to the next three right-handed hitters in the new look lineup, things begin to look pretty bleak:

- Edwin Encarnacion is hitting .240/.308/.447

- Troy Tulowitzki, while hotter lately, is still hitting just .205/.286/.391

- Russell Martin has a paltry line of .172/.237/.180, with only has one extra-base hit (ONE!!!).

Those guys need to turn things around. All of them have track records of success, so we should expect some return to normalcy, but we’re getting deeper and deeper into the season. Just last week we passed the quarter mark of the season, so time it ticking away fast.

So the question that must be answered is…why? Why are these normally excellent hitters having so much trouble in the early going? There are probably many reasons, but one of them could be that they’re being pitched completely differently than they were last year.

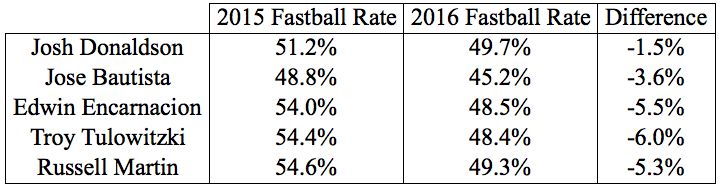

The 2015 Blue Jays feasted on fastballs. As a team, they hit a league-best .297/.378/.513 against the hard stuff. That’s pretty typical of teams with big power, and the Blue Jays were certainly one of those. Well…teams have adjusted. In the chart below, you’ll see the rate at which opposing pitchers have thrown fastballs to the five right-handed hitters listed above.

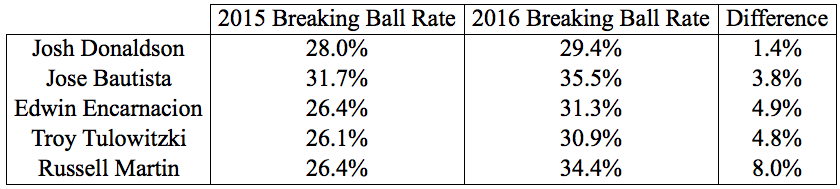

What’s interesting however, is what the teams have been doing instead. The fastballs aren’t being replaced with changeups. Instead, each of those hitters is seeing way more breaking balls than ever before.

With the exception of Donaldson, all of those hitters have seem an increase in breaking balls of 3.8 percentage points or more, with Russell Martin seeing a rise of 8 percentage points. Those are drastic changes. It’s also not one pitch that is being thrown more across the board. Donaldson, Bautista, and Tulowitzki have seen more curveballs, while Encarnacion, and Martin have each seen more sliders.

This fits with the numbers. Relative to his overall production, Donaldson has struggled on curveballs the last two years, with OPS’ of .535 and .655 against the pitch, respectively. Similarly, Bautista put up a line of .180/.268/.400 against hooks in 2015. Tulo has also had his issues against curveballs, with a career line of .248/.285/.402, including a horrible .371 OPS against the pitch last year.

As for the other two, Encarnacion has a career .221/.277/.417 line against sliders, and Martin has “hit” an awful .183/.240/.241 against those hard breakers. He’s not much better against curveballs either (.216/.291/.324), which is why he’s seeing an increase in both. League average for both pitches is between .650 and .675 OPS, and these numbers (other than Martin) are all around that mark, but these hitters are much better than “average” normally. Pitchers are exploiting the things areas that make these special hitters normal.

If you look back at those pitch usage charts, you’ll notice that both Donaldson and Bautista have seen the smallest changes in repertoire. The reason, and this is what separates them from the rest of the pack, is that they have adjusted to the new plans of attack. Donaldson is mashing curveballs this year, to the tune of .263/.364/.737, and Bautista has upped his line to .267/.333/.400. It’s not a huge increase, but he has dropped his swing and miss rate from a career rate of 26.4 down to 15.4 percent this year, and his chase rate from 12.9 to 6.3 percent. While the numbers haven’t gotten huge the way they have for Donaldson, Bautista has clearly adapted to the curveball pattern.

Also, as mentioned previously, Tulowitzki is starting to come out of his slump. A big part of the reason is that he’s making adjustments. In his last 10 games, Tulo has increased his contact rate on curveballs from 46.2 percent to 71.4 percent, and more importantly, has seen his called strike rate drop from 34 percent to 15.8 percent. It’s only 26 pitches, but he is clearly not being fooled as much by hooks as he was early in the season. In that time, he has put them in play four times with three hits, including a home run.

Unfortunately, it’s not just numbers on breaking balls that get affected by an increase in their usage. The change in pitch rates also has an effect on fastballs. Because hitters are forced to guess a bit more, they are often late on hittable fastballs. Martin and EE have seen their swing and miss rates on heaters rise by 71.5 (12.3 to 21.1) and 24 percent (16.7 to 20.7), respectively. That’s a huge jump, and fits with what we have been seeing this year. The Blue Jays have missed a lot of pitches they normally crush. Tulo has had similar issues, swinging and missing at fastballs far more often (23.3 percent vs 14.4 for his career), but once again has turned things around lately (down to 10.6 percent).

As for JD and Joey Bats, they have seen almost no change in whiff rates, as they have missed on fastballs within one percentage point of last year’s numbers. They have recognized what is happening to them, and as such, they are still producing.

Baseball is always a game of adjustments. Hitters switch up their game to attack pitchers, then pitchers switch things back. It’s a constant game of cat and mouse, and the great hitters/pitchers are the ones who can figure it out fast enough. Donaldson, and Bautista are great hitters. Encarnacion is too, and has a history of adjusting to pitchers as the season moves along. Tulo seems to be coming around the corner (though in a small sample), so that just leaves Martin (who has much less of a track record). If he can start to alter his approach, and Devon Travis provides any offense at all, this offense could take off very soon.

Lead Photo: Jesse Johnson-USA TODAY Sports

Numbers current as of the start of May 24.

It’s very exciting to think so, but man, it’s getting hard to believe so.

Full disclosure: I am a weak hearted, yellow-bellied, lily livered fan. But I do turn around fast when the team does.

I don’t know how much stock to put in this. A 5% decrease in fastballs seems pretty significant, but if I think in terms of a hitter seeing ~20-25 pitches per game, it’s only about 1 fewer, with a corresponding increase of 1 breaking ball. I’m not saying this difference doesn’t matter, just that it doesn’t intuitively seem like nearly enough to explain more than a portion of how much the bats have declined v. last year.

Excellent point! What is hard for me to reckon from the numbers is why any so-called adjustments are being made now rather than, say, halfway through last season when the Jays were feasting on pitching. Opponents know something now that they didn’t know then? Hmmmm. And it hardly requires a quarter of a full baseball season for elite players to come to terms with fewer fastballs. The ratios quoted above seem — as you suggest — interesting but not causally evaluative.

I wouldn’t say they’re not causally evaluative. While can’t actually know that one way or the other, the fact is that the attack plan has changed, and it’s the only clear change to date from their big season last year (aside from awful sequencing – they can’t hit with runners in scoring position all of a sudden).

As for a quarter of the year, that’s sort of the point I was making. JD, Bautista, and it seems Tulo, have made the adjustment. EE typically makes in-season tinkers, but is behind so far this year. Martin is the only one with any real worry, because you can see even just watching him, he has NO approach at the plate.

I think the greatest value could be that before all of them were seeing fastballs more than half the time, now they’re not. So they went going in there with a better than 50% chance that any pitch was going to be a fastball (goes up/down depending on count, of course), whereas now it’s better odds that it will be a breaking ball.

I get what you’re saying and I don’t completely rule it out as a factor, but if I sat FB last year when I saw, on average, about 12 per game out of 23 total pitches, how much need is there to change my approach because I’m only seeing 11 this year? And how much drop in performance can I reasonably attribute to seeing that 1 different pitch per game?

I don’t know what, but my gut says there’s a good deal more going on.

Does this include splits?

Sorry for the half comment above…What I mean is that you can’t just look at pitch breakdown regardless of counts. E.g. if you’re making lousy contact and don’t get your fastball in a hittable location early in the count (as is happening to Martin) then you’re going to see a lot more breaking balls because that’s what pitchers throw in the 2-strike counts where you always find yourself. It’s not really that pitchers have changed anything in terms of their approach, it’s just that the at-bats end up being ripe for chase pitches a lot more often.

Same with the horrible numbers against breaking balls…it’s not just the pitch itself, it’s that they’re seeing ones that bounce when they have to defend the plate with 2 strikes because they’re not hitting as well and ending up in those counts for whatever reason. It’s not so simple as to say the key was to simply throw more breaking balls because that’s what they have trouble hitting. The key might very well have been getting to 2-strike counts when it makes sense to throw those breaking balls for a bunch of reasons (don’t have to worry about falling behind, hitter is in swing mode) — which is a much harder thing to do, and a much more complicated thing to figure out why is happening this year.